Legislative Report: Do or Die Time for Bills Affecting Oregon's Food System

With the end of the 2025 Legislative Session a little over a month away, it's do or die time for some important bills affecting our food system to make it over the finish line. Here's an update and some actions you can take to help make that happen:

Small Farm Water Access (HB 3372). There was some very good news about this bill that would allow commercial sale of food and farm products grown using water from domestic wells, as long as the garden is one-half acre or less and with a daily gallon limit. It passed out of the House Committee of Agriculture, Land Use, Natural Resources and Water last week and just has a couple of minor steps to get it to the governor's desk. Another good thing is that an exclusion was included barring use of water from the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area which has been polluted by agricultural nitrates from factory farms and is the subject of a lawsuit.

Food For All Oregonians (SB 611). This bill envisions an Oregon where all people have access to food no matter where we were born. The FFAO coalition will introduce a bill in the 2025 legislative session. This game-changing policy will:

- Make food assistance available to young kids (ages 0-6) who are currently excluded solely due to immigration status.

- Help families pay for groceries in a way that mimics the federal SNAP food assistance benefits.

- Pave the way for future legislation that will ensure everyone of any age has access to food assistance regardless of their immigration status.

TAKE ACTION: Sign this letter to let your legislators know you believe all Oregonians should have access to food.

Groundwater Quality Protection Act (SB 1154). This bill is a much-needed update to the Groundwater Quality Protection Act and would help bring down pollution in Oregon’s four GWMAs. In Eastern Oregon, the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area (LUBGWMA) has water that is so polluted, it is unsafe to drink and is causing a public health crisis in the region. Despite this region being declared a GWMA 35 years ago, pollution continues to worsen because the Groundwater Quality Protection Act does not give state regulators the authority to require mandatory action to bring down pollution.

TAKE ACTION: Tell Oregon Governor Kotek to keep SB 1154 strong and not let Big Ag water it down.

Eelgrass Action Bill (HB 3580). Eelgrass, those green blades you see waving in tidal waters or draped languorously over rocks at low tide, are biodiversity hotspots, carbon sinks, and nursery habitat for many juvenile fish species, including those that are part of our food system. Their health is vital for sustaining our fisheries, maintaining water quality, and buffering against climate impacts. HB 3580 would fund the Department of Land Conservation and Development and the Department of State Lands to lead a task force to address eelgrass loss and improve management through a collaborative effort involving agencies, Tribes, scientists, local communities, and others.

TAKE ACTION: Sign on to this letter to the Joint Committee on Ways and Means and the Subcommittee on Natural Resources requesting their support on this important bill.

Rocky Habitat Stewardship Bill (HB 3587). Oregon’s rocky habitats, like Haystack Rock and Coquille Point, are iconic tourist destinations for millions of visitors. They are also incredibly important for millions of nesting birds, marine mammals, fish—including some that are part of our food system—and invertebrates. Increasing climate impacts and human disturbance are threatening these special places and this bill would provide needed agency coordination to build community programs to better protect these sites.

TAKE ACTION: Sign on to this letter to the Joint Committee on Ways and Means and the Subcommittee on Natural Resources requesting their support on this important bill.

State Meat Inspection (

State Meat Inspection ( Food for All Oregonians (

Food for All Oregonians ( Farm to School Program (

Farm to School Program (

Small Farm Water Access

Small Farm Water Access Conservation of Working Lands

Conservation of Working Lands

Housing: Loss for Farmers and Agricultural Lands, Win for Developers

Housing: Loss for Farmers and Agricultural Lands, Win for Developers

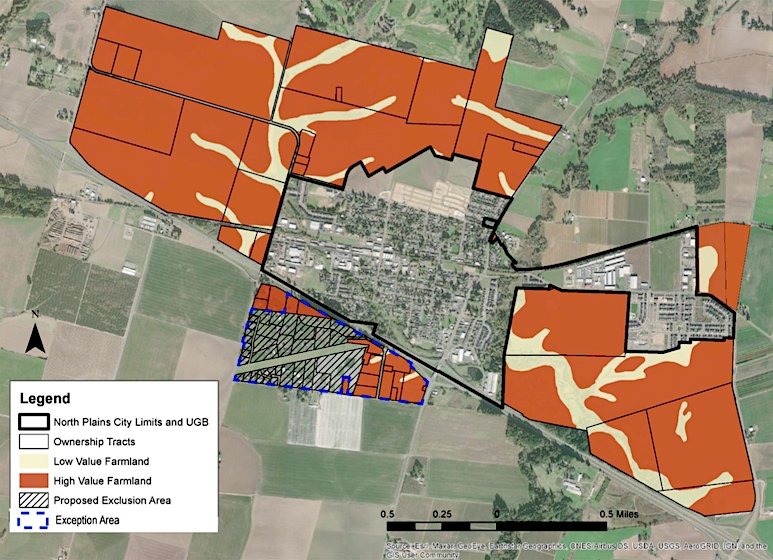

Preserving Agricultural Lands

Preserving Agricultural Lands

And indeed they did! I’ve never been at a gathering as truly diverse as this one—people young and older, from just about every part of the world, of every hue, and dozens of nationalities. Lucky for me, all speaking English albeit with the chiaroscuro of both their first language and the accent of whoever schooled them in English.

And indeed they did! I’ve never been at a gathering as truly diverse as this one—people young and older, from just about every part of the world, of every hue, and dozens of nationalities. Lucky for me, all speaking English albeit with the chiaroscuro of both their first language and the accent of whoever schooled them in English. I certainly wasn’t the only person among the 2,500 futurists who centers on healthy ecosystems—including healthy, prosperous humans, of course—but it’s also true that many of the panels and discussions at the conference were about shiny new things. Shiny new tools, shiny new technologies, shiny new approaches to problems. I told anyone who would listen that I’m not opposed to the new and shiny—unless those innovations are aimed at hacking the natural world for the convenience of humans.

I certainly wasn’t the only person among the 2,500 futurists who centers on healthy ecosystems—including healthy, prosperous humans, of course—but it’s also true that many of the panels and discussions at the conference were about shiny new things. Shiny new tools, shiny new technologies, shiny new approaches to problems. I told anyone who would listen that I’m not opposed to the new and shiny—unless those innovations are aimed at hacking the natural world for the convenience of humans.

As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting

As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting