It's Baaaaack: Hillsboro (Again) Attempting to Annex Farmland

My latest CSA update from Aaron Nichols of Stoneboat Farm in Hillsboro on what to expect in our share included this note:

"As a lot of you know, I spend some of my extra time working to protect farmland around my farm that is consistently under threat of development from data centers and other industrial uses. Unfortunately, it appears that another very big threat to 1,800 acres of Oregon's very best farmland (that is almost visible from my farm) is looming. There is a legislative concept [a draft idea for legislation before it is introduced as a bill] that has had a hearing in Salem that would make the land available for development…despite the city and the state having promised it would stay in farming for at least another 40 years."

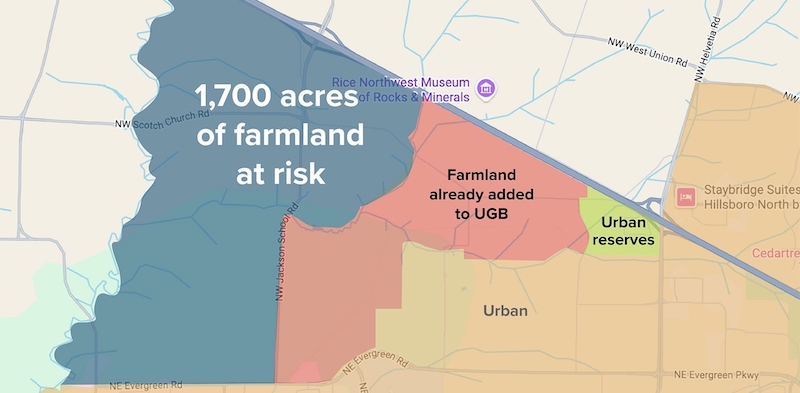

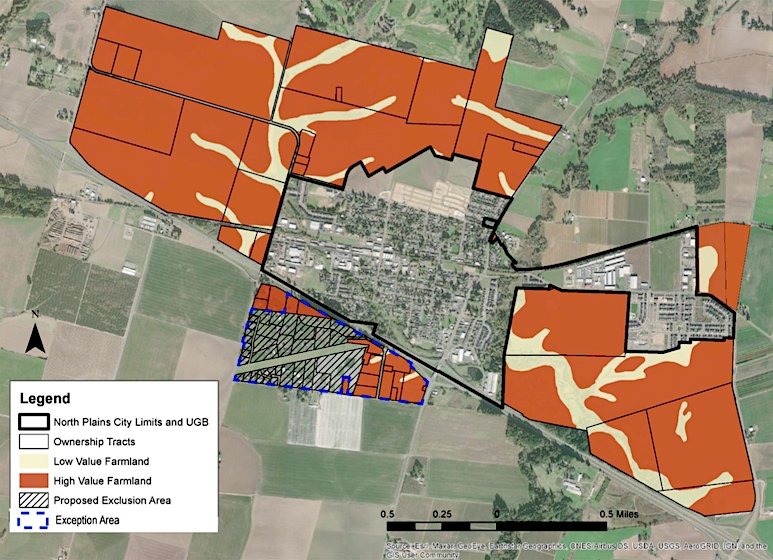

If this sounds familiar, you're not wrong. Just last July I wrote that the city of North Plains outside of Hillsboro had "attempted to double the size of the city by proposing the biggest-ever Urban Growth Boundary (UGB) expansion by percentage basis and the largest by acres in the metro counties." The voters of North Plains responded by rejecting the city's ballot measure by a margin of 70 percent.

Well, now it's Hillsboro's turn to take a turn at snatching what has been described as some of the richest farmland in the area, and this time they've upped the ante to four times the size of the North Plains grab.

Oregon has a rigorous process for expanding the UGB that this proposal attempts to shortcircuit. Rather than basing economic policy on verifiable needs, the so-called "Oregon JOBS Act" (LC 237) proposed by Hillsboro state senator Janeen Sollman sets a precedent of awarding land on a “who you know” basis. According to land-use advocates at Friends of Smart Growth, landowners in the area have been trying for years to get their land added to the UGB—not because it serves the public interest, but because their land value would increase by 50 times. The Smart Growth website says "the precedent set by this proposal would lead to a mishmash of laws and an unpredictable regulatory climate for businesses in and out of the UGB and would set aside the rule of law in favor of a system that is open to corruption and mismanagement."

For perspective, figures from the 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture show that the number of farms in Oregon decreased by six percent since 2017, and the acreage those farms occupied was down four percent in the same period. 1000 Friends of Oregon detailed that only about 16 percent of Oregon (excluding federal lands) consists of high-value soils, with only about four percent of those rated as prime farmland, and that efforts like the one proposed in this legislative concept endanger those remaining valuable soils.

The threat these data centers pose isn't limited to Oregon's diminishing agricultural land. According to an article in The Guardian, while data centers consume just one percent of the world's electricity now, "their share of U.S. electricity is projected to more than double to 8.6% by 2035."

1000 Friends points out that corporate data centers—the kind of industrial development most often discussed for this parcel—which are touted as super-charging job creation, actually create few, relatively low-paying jobs. Furthermore, it goes on to say that "the bill that Hillsboro state senator Janeen Sollman is proposing will extend tax breaks for these same corporations—companies that can easily afford to pay their fair share.

"Meanwhile, the state is slashing social services budgets that help keep Oregon’s working families afloat, [and] data centers are expected to increase PGE and Pacific Power rates by 50 percent in 5 years (despite the passage of the POWER Act), fresh water is being used and polluted by data centers, and data centers are costing Oregon hundreds of millions in tax revenue each year. Clearly, this industry is not benefiting most Oregonians."

ACTION ITEMS: There are several actions you can take on this issue.

- Click here to send an e-mail to your elected representatives.

- Attend the community meeting and information session: Jan. 30th, 5-6 pm; United Church of Christ, 2032 College Way, Forest Grove.

- Attend Sen. Sollman’s town hall (across the street from the community meeting) immediately following the information session at 6:30 pm; Pacific University’s McCready Hall in the Taylor‑Meade Performing Arts Center, 2043 College Way, Forest Grove.

State Meat Inspection (

State Meat Inspection ( Food for All Oregonians (

Food for All Oregonians ( Farm to School Program (

Farm to School Program (

Small Farm Water Access

Small Farm Water Access Conservation of Working Lands

Conservation of Working Lands

Housing: Loss for Farmers and Agricultural Lands, Win for Developers

Housing: Loss for Farmers and Agricultural Lands, Win for Developers

Preserving Agricultural Lands

Preserving Agricultural Lands