The following essay is by Angel Medina, an "award-winning writer, filmmaker, and restaurateur; lover of coffee and mezcal; founder of TODOS Media; co-owner of República & Co." according to his bio on Substack. His recent newsletter, Between Courses, dropped in my in-box and I was in tears reading it. I immediately wrote to ask if I could share it with my readers. He generously agreed.

When Hospitality Becomes a Hunting Ground:

Why I'll Close Before I Collaborate

In occupied Paris during the Second World War, the city’s great cafés and dining rooms took on an uncanny second life.

At Le Meurice, just across from the Tuileries, German officers planned operations beneath chandeliers designed for diplomats, artists, and foreign ministers. Rooms meant for elegance became rooms for strategy. Velvet absorbed conversations it was never meant to hear.

At the Ritz Paris, Hermann Göring and other high-ranking Nazi officials dined lavishly while the rest of the city survived on ration bread, turnips, and silence. Inside, crystal glasses caught the light. Outside, Paris starved.

On the Left Bank, brasseries like La Coupole; once a refuge for writers in the 1920s and ‘30s, for painters, late-night arguments, smoke-filled conversations that stretched until morning—appeared in German guidebooks as approved establishments for Reich officers. These weren’t rumors. They were printed. Mapped. Sanctioned.

These were not makeshift spaces. They were temples of French hospitality.

Tables set for oysters, red Burgundy, sole meunière—menus printed in careful French script—were read by men in gray-green uniforms speaking the language of orders, borders, and control. Outside, Paris was hungry. Inside, the wine poured.

And for the people of Paris—the waiters, the cooks, the porters, the women emptying ashtrays, polishing cutlery, carrying glassware through rooms thick with smoke—occupation was lived at eye level.

To serve was framed as an honor. In reality, it was survival. To refuse meant disappearance.

Every plate carried across those rooms required a careful calibration between obedience and restraint. You learned how to keep your eyes down. You learned how to move quietly. You learned how to pretend you couldn’t hear the conversations happening inches from your body—conversations about raids, decrees, futures that did not include you.

You learned how to endure the presence of men dismantling your country one regulation at a time.

The restaurants stayed open. But nothing about them was normal.

When I think about this now, I think about Casablanca—released in 1943, right in the middle of all of it. There’s a scene at Rick’s Café where German officers raise their glasses and sing Die Wacht am Rhein with patriotic zeal. The rest of the room—locals and refugees alike—sits frozen, watching. A song. A toast. A performance of normalcy.

It looks like leisure. It sounds like celebration. But every note carries threat.

That scene stays with me because it understands something essential: power doesn’t always announce itself with violence. Sometimes it sings. Sometimes it eats. Sometimes it pretends to belong.

Last week, four ICE agents walked into El Tapatio, a small, family-owned Mexican restaurant in Willmar, Minnesota. They sat down at a booth. They ordered lunch. They ate like anyone else on an ordinary afternoon.

People in the kitchen noticed them. Maybe someone thought—or hoped—that this meant something. That they were normal enough to come in, order food, enjoy a meal.

Hours later, after the restaurant closed, those same agents followed the staff outside and detained three of them.

There was no battle. No courthouse summons. No warning.

Just their meal—and when they were finished, the hunt.

This wasn’t isolated. It’s part of what’s been described as Operation Metro Surge—thousands of federal agents deployed across Minnesota. Whether you want to call it retaliation, or politics, or a vendetta against officials who spoke too loudly or protected their communities too fiercely almost doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is the result.

Immigration enforcement has expanded dramatically and indiscriminately. Minnesotans report ICE presence in schools, restaurants, community spaces that were never meant to be policed this way. Flights leaving the state with detainees have increased. Fear moves faster than facts.

And that fear doesn’t stop at immigration status. It spreads—to families, coworkers, neighbors, business owners. To people just trying to live without constant surveillance. Even to people who voted for this administration. Power, once unleashed, doesn’t check who supported it.

El Tapatio now bears a simple sign on its door: Closed for online orders only.

If that’s not a symbol of a community disrupted, I don’t know what is.

There is an unspoken understanding in hospitality that a meal shared, a table set, is not a prelude to harm. Hospitality is trust embodied. It’s the belief that for the duration of a meal, you are safe. That service is not consent. That feeding someone does not make you complicit in your own undoing.

When that line is crossed, it doesn’t just break the law. It breaks a bond.

Minnesota is not an outlier. It’s a rehearsal.

This administration has mentioned Portland more than once as a place that needs to be “fixed.” A city they’ve floated the idea of sending troops into. If you know Portland, you know how dangerous that thinking is.

The fragility of this place isn’t something you learn from books or policy memos. You learn it by living here. We watched it happen in real time. We saw how quickly a sidewalk became a flashpoint, a park became a perimeter, a café became a line of sight.

Cities don’t collapse all at once. They fray. Quietly. One room at a time.

And restaurants are not neutral ground—not here. They’re where people go when they’re tired, hungry, looking for warmth, recognition, a moment of being seen without explanation. They’re where birthdays are celebrated, grief is held without ceremony, conversations happen that don’t survive fluorescent light.

A table is a promise.

You sit down believing—even if only for an hour—that nothing bad will happen to you there.

Community is sustained at those tables. Not just by food, but by the rhythm of voices, the scrape of chairs, the way laughter rises and falls like weather. By the understanding that the people cooking your food and clearing your plates are not abstractions. They’re neighbors. Parents. Documented, undocumented, and everything in between. Lives far larger than a shift number on a screen.

History keeps reminding us how easily that promise can be broken.

It doesn’t start with sirens. It starts with presence. With people who sit down and order. With uniforms that try to disappear into the room.

And when hospitality becomes reconnaissance, the room changes. Refuge becomes risk. Livelihood becomes calculation. The question becomes: Is it safe to come in today?

If federal agents begin treating our restaurants as hunting grounds—dining at our tables and returning later to detain, surveil, or intimidate the people who make these spaces live—I will not keep the doors open.

At that point, staying open becomes participation. Silence becomes consent.

There is a difference between enforcement and intimidation. One operates in daylight, accountable to process. The other relies on fear, surprise, and humiliation. There is a difference between law and cruelty—even when cruelty wears a badge. And there is a profound, unforgivable difference between sharing a meal and setting a trap.

I will not ask my staff to enter rooms where the air itself feels compromised. I will not ask them to smile, to serve, to move through their day knowing the people who asked for another round might be waiting outside. I will not normalize terror by calling it policy or the cost of doing business.

Once hospitality becomes a mechanism of harm, it ceases to be hospitality at all. It becomes theater—a stage where power rehearses itself while the most vulnerable are forced to perform calm.

This is not what we signed up for when we opened our doors.

This is not what care is supposed to be used for.

I know there are people in power who would love to see this city fail, who would love to see its communities fracture, who would love to march through our streets and mistake fear for control.

But for me, that’s where the line is drawn.

Some things are more important than staying open. Some things are more important than revenue. And some things are more important than service.

Dignity is one of them.

Postscript: On January 28, 2026, Medina announced the closure of his beloved República for reasons he explained in a post, writing that "one issue rose above all others. When the safety of my staff; people who built this place with their hands and their memories—could no longer be assumed, when their dignity and security were treated as negotiable, silence stopped being an option. We stayed quiet for a year, hoping things wouldn’t worsen. They did. And they will continue to."

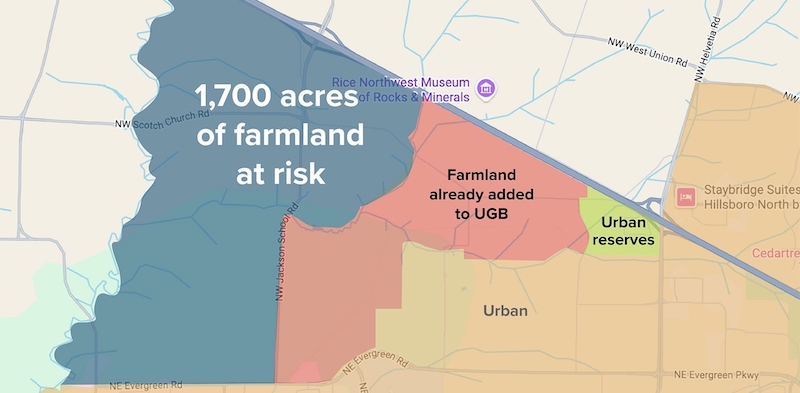

Farm Store Bill (

Farm Store Bill ( Disproportionate cuts to OSU Statewides & Organic Agriculture Program: Due to a budget shortfall of $63 million, the legislature is proposing a one percent to five percent cut to most agencies, but the OSU Statewides Programming, which includes the Organic Agriculture Program, is facing a 7.1 percent cut. Advocates, while acknowledging the need to trim budgets, are asking the legislature to "rightsize" the cuts to the program to match those being asked of other agencies. The Organic Agriculture Program at OSU now has six extension specialists across cropping systems working throughout the state, working to enhance the viability of Oregon agriculture through improved soil health, cover crop adoption, ecological pest management, locally adapted cultivars, farm viability, and transition to organic and other ecological methods.

Disproportionate cuts to OSU Statewides & Organic Agriculture Program: Due to a budget shortfall of $63 million, the legislature is proposing a one percent to five percent cut to most agencies, but the OSU Statewides Programming, which includes the Organic Agriculture Program, is facing a 7.1 percent cut. Advocates, while acknowledging the need to trim budgets, are asking the legislature to "rightsize" the cuts to the program to match those being asked of other agencies. The Organic Agriculture Program at OSU now has six extension specialists across cropping systems working throughout the state, working to enhance the viability of Oregon agriculture through improved soil health, cover crop adoption, ecological pest management, locally adapted cultivars, farm viability, and transition to organic and other ecological methods. Budget for Programs in the Immigrant Justice Package:

Budget for Programs in the Immigrant Justice Package:

Food System

Food System Justice for Immigrants and Farm Workers

Justice for Immigrants and Farm Workers Environment and Climate

Environment and Climate