Drought Plus Fire: A Devastating, and Potentially Deadly, Combination

Cory Carman of Carman Ranch is a pasture-based rancher on the land in Eastern Oregon's Wallowa County that her family has passed down over four generations. Her story brings visceral meaning to the words "drought" and "fire."

“Dry” was the word we used at the start of the growing season. The plants barely grew, their normally vibrant colors signaling spring and early summer strangely muted. The land I know so well felt completely unfamiliar.

It didn't rain. We began to say “drought,” a word that invokes a certain level of anxiety and urgency. It was time for action, but what to do? And when to do it? Our ranch manager, Sam, and I spent hours revisiting our grazing plan and forage budget. Should we sell cattle? Which ones, and when? If we did, would we be able to serve our customers? Pay our bills?

It didn't rain. We began to say “drought,” a word that invokes a certain level of anxiety and urgency. It was time for action, but what to do? And when to do it? Our ranch manager, Sam, and I spent hours revisiting our grazing plan and forage budget. Should we sell cattle? Which ones, and when? If we did, would we be able to serve our customers? Pay our bills?

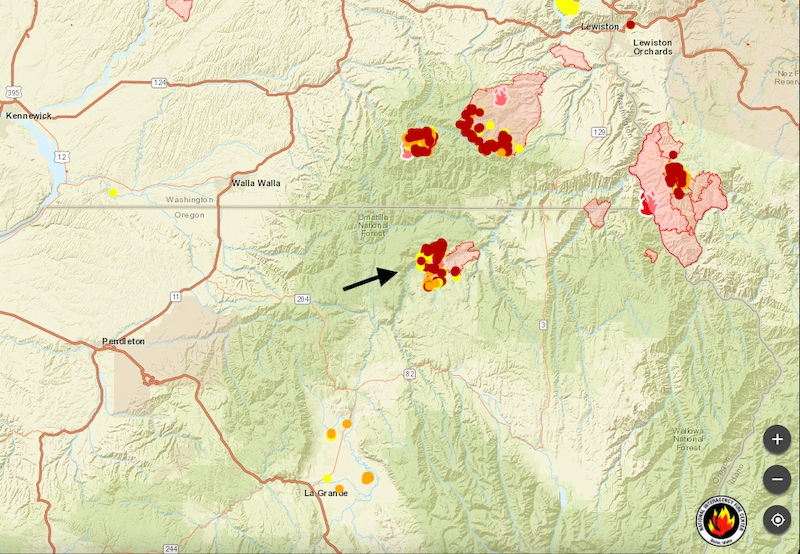

Then the storm clouds rolled in, not with rain, but with lightning. It struck in the dense timber north of where we were running 320 pair. We watched the fire grow, traveling across the gnarly country toward the cattle. To gather and keep them bunched together would make it easier to evacuate them, but to do it too soon would mean leaving them for a period of time that would stress the land. To wait too long might put us in danger.

I reached out to Ed, a public information officer from the Lick Creek Fire, as it came to be called. Ed was from a very competent national team sent to help manage the blaze. We discussed the location of cattle, the progress of the fire and devised a plan.

He told us the fire crews were attempting to hold the southern line of the fire (at that point 50,000 acres) along two forest service roads. If we could consolidate the cattle into one large pasture, we would be able to gather them in a day. If the fire crossed the road to the steep, rugged terrain, thick with timber, they wouldn't be able to stop it until it reached the cattle. It would take more than a day for the fire to travel the 7 miles to the cattle, leaving us time to get them to safer ground. We had a plan.

He told us the fire crews were attempting to hold the southern line of the fire (at that point 50,000 acres) along two forest service roads. If we could consolidate the cattle into one large pasture, we would be able to gather them in a day. If the fire crossed the road to the steep, rugged terrain, thick with timber, they wouldn't be able to stop it until it reached the cattle. It would take more than a day for the fire to travel the 7 miles to the cattle, leaving us time to get them to safer ground. We had a plan.

So last Monday (7/12) night, Sam, my 13-year-old son Emmett, and two other riders hauled the horses two hours to the ranch house where we lease the pasture. They set up cots, slept a little, and were at the pasture at daylight. I met them that morning with food and water. Together, we gathered the cattle until late afternoon.

Back at the ranch house, Emmett fell asleep before he could finish eating his sandwich. While he slept, we checked the rest of the cattle and headed back, feeling like we'd executed the first part of the plan.

The next morning, I called Ed to see what the fire did overnight. For two days, the crew held the southern line through back-burning and we began to breathe a sigh of relief. Then, on Thursday (7/15) afternoon, we heard rumors that another fire had started to the west and it was moving quickly toward the cattle. The fire (later named the Elbow Creek Fire), was gathering speed, burning on both sides of the Grande Ronde River.

Exceptionally dry conditions and the steep terrain overwhelmed local fire crews quickly. With four active wildfires in the region, not including one of the largest in Oregon history—the Bootleg Fire in Southern Oregon—there was very limited help to send. Ed called after his briefing. His tone had changed and, reading between the lines, it was clear he didn't know if they would be able to stop this fire. He suggested we move our herd of cattle closest to the new fire out of the area.

Exceptionally dry conditions and the steep terrain overwhelmed local fire crews quickly. With four active wildfires in the region, not including one of the largest in Oregon history—the Bootleg Fire in Southern Oregon—there was very limited help to send. Ed called after his briefing. His tone had changed and, reading between the lines, it was clear he didn't know if they would be able to stop this fire. He suggested we move our herd of cattle closest to the new fire out of the area.

That evening, Sam went home, saw his wife and 2-year-old son, and loaded up the horses. I grabbed food and water and headed out, this time leaving Emmett home. We called Marvin, one of our favorite truck drivers, and asked him to meet us at the corral in the morning.

When we gathered at daylight, it was beautiful and crisp, but the huge columns of smoke to the north and the west made what would have otherwise been an enjoyable task surreal. At 6:30, Marvin arrived and we loaded the truck with 33 pairs, then traveled several miles to the next group of cattle, to consolidate them into a smaller pasture. We took a break in the heat of the day, when the cattle were so deep in the brush we had to walk right into one to find her.

We came back in the evening, finishing up by moonlight. We did the same thing the next day. When Marvin arrived at 6:30, we loaded out the last of the smaller herd, before we finished collecting the cattle we missed the day before. The timber was so dense that it sometimes felt like luck to find any at all. I glanced at a wolf pup and kept searching. The smoke made the temperature more bearable, and we were able to gather all but two of the cows in a 200-acre pasture, with good water and enough feed to allow us time to see what the new fire would do.

It’s been five days now, and the Elbow Creek fire hasn’t moved much closer to our cows, instead heading west and—almost ironically—south, towards the ranch where we brought the first two truckloads and where my kids and I live. When I look out our front window, there's a sea of tents and porta potties, and a helipad two fields in the distance. During the most recent briefing, we were told that there were over 1,000 firefighters on this fire, more than doubling the Wallowa's population of 805.

The drought set up the conditions for these fires, each of which has caused us to consider our relationship to our animals in a new context: In times of stress, we forfeit good management and a grazing plan in favor of being able to leave quickly. When there's no rain, we have to compromise our goal of constantly moving cattle to green and lush pastures, and think about how many animals the land can support.

This isn't over yet, but I've come to realize along the way that we can't control or obsess over the financial implications. Every time I worry about how we’ll make our budget work, or if we'll be able to pay down our operating loan, I go down a path that ends with decisions that are ultimately detrimental to our people or our land. And those are relationships that can't always be repaired. Digging out of a financial hole can be time consuming, but it’s possible. And in a year like this, something has to give.

My relationships with the people who care for our animals are ones I hold most dear. And also the myriad relationships with customers and friends in the culinary community, who have texted and emailed and called. There's no doubt that this will continue to be a challenging year, and so we'll keep looking for different ways to make it work. As I have before, so many times in this business, I am finding all the solace I need from you, the people who support us and have our backs.

Thank you.

Read my interview with Cory Carman about why she chose to raise her animals on pasture, and how she sees it as a vital tool in reversing climate change and building a more resilient and vibrant local food system.

If you’re interested in what’s happening in large-scale meatpacking plants,

If you’re interested in what’s happening in large-scale meatpacking plants,  Kalapooia has nearly perfect marks on its annual food safety audits, and on a comprehensive animal welfare audit. Built by Reed Anderson (right, center) to process his own Anderson Ranch lambs, Reed also processes cattle for a few companies, including Carman Ranch. Reed’s son Travis oversees day-to-day operations, and I’ve worked with Pete, Kalapooia's plant manager, for over a decade. The Andersons think of their processing plant as a family business, an ethos that extends to include their staff and customers. Anderson Ranch employs fewer than 50 people, and they took the safety of their workers seriously early on in the COVID outbreak, in part because Pete and Travis work side-by side on the line with their employees. They already required protective clothing, and their small size allowed them to create distancing more easily and effectively than larger plants.

Kalapooia has nearly perfect marks on its annual food safety audits, and on a comprehensive animal welfare audit. Built by Reed Anderson (right, center) to process his own Anderson Ranch lambs, Reed also processes cattle for a few companies, including Carman Ranch. Reed’s son Travis oversees day-to-day operations, and I’ve worked with Pete, Kalapooia's plant manager, for over a decade. The Andersons think of their processing plant as a family business, an ethos that extends to include their staff and customers. Anderson Ranch employs fewer than 50 people, and they took the safety of their workers seriously early on in the COVID outbreak, in part because Pete and Travis work side-by side on the line with their employees. They already required protective clothing, and their small size allowed them to create distancing more easily and effectively than larger plants.  As we move through this crisis, we’re learning more about the vulnerabilities in our incumbent systems. Affordability in food is important, but saving a few dimes can come at a cost none of us should have to shoulder, including our own health and safety. Across the country, those costs are now coming to light.

As we move through this crisis, we’re learning more about the vulnerabilities in our incumbent systems. Affordability in food is important, but saving a few dimes can come at a cost none of us should have to shoulder, including our own health and safety. Across the country, those costs are now coming to light.

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.

While Carman respects her family’s history and that of her neighbors, she is pursuing the inverse of the methods used on most of the nation’s cattle ranches since the middle of the last century—methods also used by her father, who died in a ranching accident when Carman was 14, and by her uncle who took over.