As you browse the bulk goods section at the store, collecting nuts and seeds from the bins or even grabbing bags off the shelves, you would do well to think about the farmer who grew them. As contributor Anthony Boutard of Ayers Creek Farm outlines below, those products we so blithely consume by the handful didn't just come from a packet of seeds scattered on the soil—indeed, they may have taken years to get to the point where the farmer considers them a viable product.

A pumpkin fruit with hull-less seeds originated as a chance mutation in the Austrian state of Styria during the 1890s. The pumpkins were grown as an oilseed since the 1740s and a sharp-eyed Styrian farmer noticed one had very different seeds. Without a hull, it was much easier to mill and press for oil so the mutation gained acceptance.

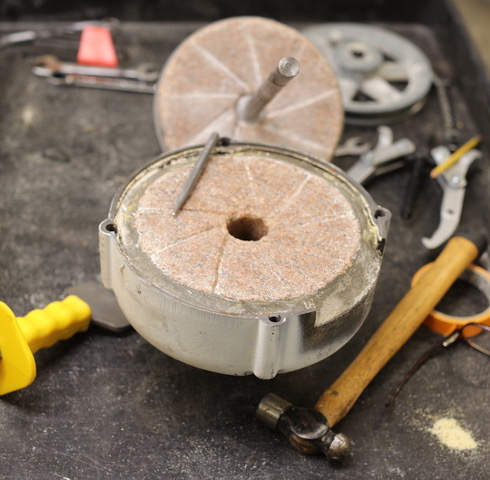

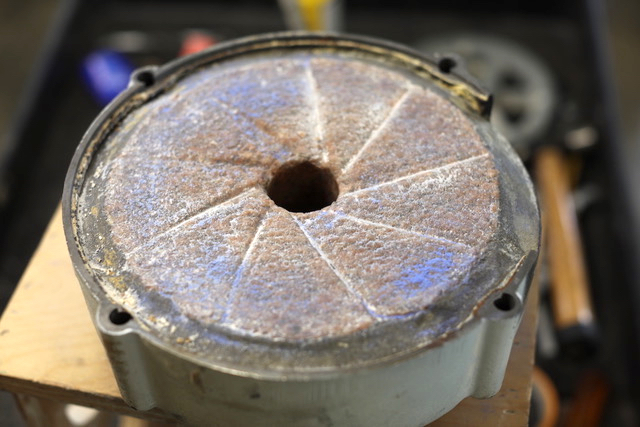

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original.

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original.

The idea of growing the hull-less seed type pumpkins for their seed came to us ten years ago. We did not have any interest in producing oil, just the seeds. Commercial pumpkin seeds in the grocery store had failed to impress; the seeds were chipped and broken, often stale and you could see they were grown and harvested without thinking of them as a fine food. Just a bunch of widgets. We thought it would be wonderful to have some good quality pumpkin seeds in the pantry.

Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits.

Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits.

Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait.

Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait.

If the seed splitting had been a cultural trait, rather than a genetic trait, we would have needed to analyze how we grow the plants and harvest the fruits. Before we settled on the genetic cause, staff argued that we were taking too long to harvest the seed and that led to split seeds. A few years ago, confident that we were on the right track, we increased our planting substantially. To save labor, in early September staff harvested the seeds in the field. We did not need to haul the fruits out of the field and dispose of the deseeded pumpkins, saving a lot of staff time.

Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.

Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.

In 2018, we planted just a few pumpkin plants. In September, we piled the pumpkins next to the harvest shed while we finished other tasks. With their hard shells, they were fine through all sorts of weather. In November, we started opening the fruits and happily there was no problem with splitting and, most importantly, the seeds were delectable from the start. Our breeding efforts were again validated, and the more patient approach to harvesting was also rewarded. Last year, we followed the same protocol with good results again.

Emboldened, we decided to double the planting this year. One rainy day in mid-September something seemed odd; there was music coming from the barn. Staff had decided to start removing the seeds from the fruits. Obviously, we had not adequately communicated the reason we left the pumpkins piled up in front of the shed. We dried the seeds hoping they would be good, but we had 28 pounds of pig food. I filled a jar of those seeds along with one containing the remnant of last years seed, and gave both jars to staff. One sniff and they understood the problem, and why it is important to wait.

In the course of two months, between mid-September and mid-November, the seeds continue developing within the fruits. Bear in mind, the fruits started growing in mid-July; so by leaving the seeds in the fruit until November we are doubling the growing time for the seeds. The pumpkin fruit is a living remnant of the plant and those seeds are drawing nutrients from the pulp. During this idyll they assemble the oils critical for their flavor. By mid-November, the seeds are measurably denser than those extracted in September, and have a fine, nutty flavor. Most importantly, no more recoiling from the odor.

We will continue to refine the genetic and cultural dimensions of our pumpkin seed production. In the meantime, we are enjoying this year’s harvest. They are delicious raw, but we like to pop them in a hot, dry skillet. The heat toasts the lovely oil and offers a pleasant crunch. Children will enjoy seeing them pop in the pan. All the popped seeds need is a pinch of salt and, just maybe, a squeeze of lime as they cool. Additional oils, fats and spices cover up their fine flavor. If they had a dull flavor or smelled like, well, you know, then it would make sense to try and add a different flavor or fragrance, but our seeds are perfect as they are.

I received a note from Carol yesterday that said, "I wanted you to see the borlotto I harvested a few days ago. I'm so glad our bean days aren't behind us!" The photo on the left was attached.

I received a note from Carol yesterday that said, "I wanted you to see the borlotto I harvested a few days ago. I'm so glad our bean days aren't behind us!" The photo on the left was attached.

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original.

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original. Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits.

Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits. Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait.

Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait. Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.

Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.