Fermenting Sauerkraut: Sauer Is as Sauer Does

As cabbage season is upon us once again, I thought it was high time to rerun this post from December, 2011. The basic technique described below is the one I still use, though I don't do the water bath canning method that Ron prefers, since I like the crunchy, fresh (and probiotic) quality of the cabbage straight from the crock—the only drawback is you need more fridge space to store it, since it's not shelf stable. C'est la vie!

If it wasn't for a teensy misunderstanding, I might have been enjoying sauerkraut long before I did. You see, my mother had been told that my father's father had come to the United States from Germany as a young man.* So, as a young wife wanting to please her new husband, she tried serving him meals that would appeal to what she thought of as his German-American upbringing.

Occasionally we would come to the family dinner table to find her version of a German dish was being featured, that is, sauerkraut straight from the jar heated on the stove with hot dogs—Oscar Meyer, no doubt—simmered in it. I think it took my father years to tell her he really wasn't fond of sauerkraut, but not before the tart, vinegary, tingle-your-back-teeth feeling was etched into all our minds.

That all changed for me when Dave and I went to France, traveling through the region called Alsace. Staying in an auberge with a fantastic restaurant on the first floor, we had the regional specialty called choucroute garnie, sauerkraut simmered for hours in a rich stock with sausages, pork, ham and other meats. It was truly a revelation, and forever changed the way I think about sauerkraut.

Which is why, when the subject of sauerkraut came up at a dinner we attended recently, I effused about my love for fermented cabbage. It turned out that the fellow I was speaking to was a sauerkraut aficionado, making gallons of the stuff every year from local cabbage, and he asked if I'd like to come observe the process. As you might expect, he'd barely finished asking when I answered, "Hell, yes."

I showed up one morning to find Ron Brey in his kitchen with several gigantic heads of green cabbage sitting on the counter. He buys them from Sun Gold Farm at the PSU farmers' market and looks for large cabbages—he buys 14 pounds total, or about three, per batch—that are tight and "hard as rocks." That amount is good for about seven quarts of sauerkraut, exactly the number of jars that will fit in his canner. He then slices the heads into quarters and then cuts those in slices about the thickness of a dime, slicing around the core.

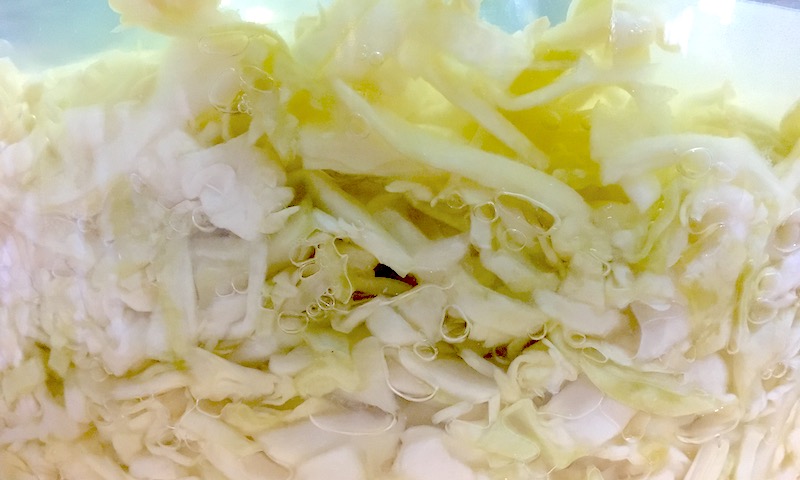

The chiffonade from the cabbage goes into a bowl and is mixed with 11 tablespoons of salt, which almost immediately starts to "sweat" the cabbage, that is, to pull the moisture out of the leaves. Ron says he uses kosher salt because it has no additives, and mixes it in gradually as he adds more cabbage. The salt and cabbage mixture is then left to sit in the mixing bowl for six hours.

After that, Ron transfers the shreds of cabbage into the glass crocks he uses to ferment the sauerkraut. (The glass-lidded glass jars are from Fred Meyer and he says they're much cheaper than most of the ceramic crocks sold for making sauerkraut.) He firmly packs the sauerkraut in the crock by hand until it's about seven-eighths full, or up to the shoulder of the crock. [It's not necessary to completely fill the crock. I've done batches with as little as 1/3 of the crock and it turned out great.]

Brey emphasizes that it's important that the sauerkraut remains submerged in its liquid in the crock, and various mechanisms have been developed to press down the shreds, some of which work better than others. But here's the genius part: Ron came up with his own method that works like a charm and is so simple it's ridiculous. He takes a gallon zip-lock bag, fills it with water, and sets it in the crock on top of the cabbage. With a gallon of water weighing in at about eight pounds, it's plenty to keep that crazy sauerkraut under control, and it conforms to the shape of the crock. Awesome!

The cover is placed on the crock, and the sauerkraut goes down in Ron's basement to ferment for a couple of weeks. He likes to keep it at 65° for the fermentation…lower than that would be fine, but would slow down the process. He says, "There is some point—certainly by 80 degrees—where it becomes increasingly likely that the kraut will not ferment correctly. It can become soft, dark and lose the combination of tartness and sweetness." The kraut should remain fairly light-colored during fermentation; any serious darkening is an indication the ferment has gone wrong and should be tossed. Ditto, obviously, with mold.

After a couple of weeks the crock is brought up to the kitchen, the kraut is transferred to clean quart glass canning jars and is canned in the same kind of water bath canner my mom used for preserving fruit. Too bad she never knew about homemade sauerkraut and that paradigm-shifting choucroute.

Ron recommends the book "Stocking Up" by Carol Hupping as a basic guide for making sauerkraut and other preserved foods. I would also recommend "The Art of Fermentation" by Sandor Katz as an excellent guide. For Japanese pickling methods, the slim but essential "Tsukemono" is unsurpassed.

* In going through some family papers, I have since found out that my grandfather was born on Oct. 2, 1891, in the town of Sitauersdorf/Sitauerowka in the region of Galicia in what was then Austria, and is now a geographic region spanning southeastern Poland and western Ukraine.