Mid-Summer Book Report: Child Brides, French Dirt, Norma Paulus

All it took to breeze through three-and-a-half books was a week spent in a rustic cabin on Mt. Hood accompanied by a spate of cooler-than-normal weather that "forced" me to spend more time indoors than out. Yes, we got out for hikes, but then retreated to the comfort of books and coffee and lapdogs.

The Secret Lives of Saints: Child Brides and Lost Boys in Canada's Polygamous Mormon Sect, by Daphne Bramham, is an exposé of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), "one of the largest of the fundamentalist Mormon denominations and one of the largest organizations in the United States whose members practice polygamy" (Wikipedia). Bramham, an award-winning journalist and author (as well as a personal friend), has been doggedly reporting on this cult for the Vancouver Sun for the last 15 years.

The Secret Lives of Saints: Child Brides and Lost Boys in Canada's Polygamous Mormon Sect, by Daphne Bramham, is an exposé of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS), "one of the largest of the fundamentalist Mormon denominations and one of the largest organizations in the United States whose members practice polygamy" (Wikipedia). Bramham, an award-winning journalist and author (as well as a personal friend), has been doggedly reporting on this cult for the Vancouver Sun for the last 15 years.

Starting with a history of the sect when it broke away from the mainline Mormon church (the Latter-Day Saints or LDS) when the LDS banned "plural marriage" in 1904, Bramham traces the evolution of the FLDS—with settlements in Utah, Arizona, British Columbia, Colorado, Texas and South Dakota, all governed by a self-proclaimed "Prophet"—to the 2007 trial and conviction of one of those prophets, Warren Jeffs, for being an accomplice to the rape of an underaged girl.

At the time of the book's publication in 2008, Bramham wrote:

"Prophet Warren Jeffs controls every aspect of the lives of more than eight thousand people, from where they live to whom and when they marry. Jeffs has banned school, church, movies and television. He has outlawed the colour red and even forbidden his followers to use the word "fun." Along with his trusted councillors, Jeffs has arranged and forced hundreds of marriages, some involving girls as young as fourteeen and men as old as or older than their fathers and grandfathers. Many of the brides have been transported across state borders as well as international borders with Canada and Mexico."

A page-turner, it chronicles the dangerously wacky, power-hungry men who turn a so-called religion to their own ends, damaging the lives of gullible men, women and children in the process. Bramham doesn't spare criticism of government officials of both countries for taking an infuriatingly hands-off approach to the commonly acknowledged abuses happening right under their noses. It's a gripping story, well-told and thoroughly documented. Highly recommended.

For something completely different, French Dirt: The Story of a Garden in the South of France, by Richard Goodman, begins with the author recalling how, as a 20-something aspiring writer, he was presented with the following classified ad by his Dutch girlfriend: "SOUTHERN FRANCE: Stone house in Village near Nimes/Avignon/Uzes. 4 BR, 2 baths, fireplace, books, desk, bikes. Perfect for writing, painting, exploring and experiencing la France profonde. $450 mo. plus utilities." With the adventurous spirit of youth, they rent the house for a year and move to a small village where Goodman is moved to start a garden on a small patch of ground loaned by a villager.

For something completely different, French Dirt: The Story of a Garden in the South of France, by Richard Goodman, begins with the author recalling how, as a 20-something aspiring writer, he was presented with the following classified ad by his Dutch girlfriend: "SOUTHERN FRANCE: Stone house in Village near Nimes/Avignon/Uzes. 4 BR, 2 baths, fireplace, books, desk, bikes. Perfect for writing, painting, exploring and experiencing la France profonde. $450 mo. plus utilities." With the adventurous spirit of youth, they rent the house for a year and move to a small village where Goodman is moved to start a garden on a small patch of ground loaned by a villager.

Far from the cutesy tales told of the quaint inhabitants of small villages in France or Italy—Peter Mayle and Frances Mayes being perhaps the best-known practitioners of the genre—this is the story of a young man falling in love with a garden and learning about himself in the process. Charming and well-told, it even received the unsolicited imprimatur of none other than M.F.K. Fisher herself:

"I possess a deep prejudice against anything written by Anglo-Saxons about their lives in or near French villages, especially in Provence. I really cannot stand the lip-licking enjoyment of local peasantry by these visitors from America and England. So, Richard, I thank you for breaking the spell. I like very much what you wrote. It did not sound supercilious at all. All my best always, M.F.K. Fisher"

I couldn't agree more.

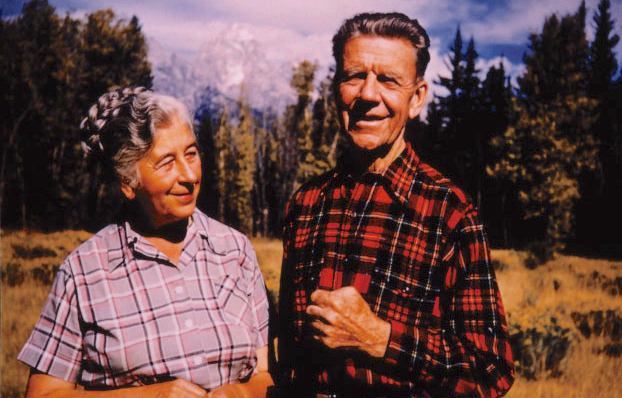

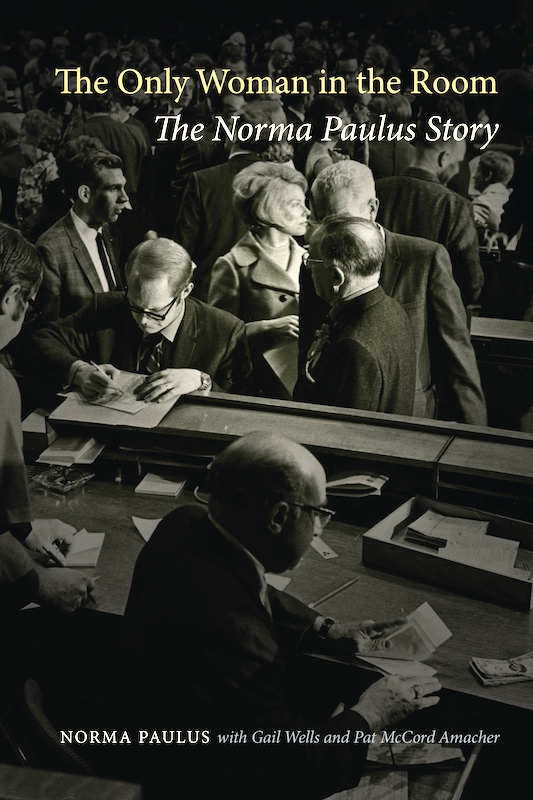

The Only Woman in the Room: The Norma Paulus Story by Norma Paulus with Gail Wells and Pat McCord Amacher, startled me on many levels. As a native Oregonian who lived through the years covered by this biography and knew many of the names and issues described in it, I was fascinated to learn of the behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing involved in some of the biggest headlines—think the bottle bill, saving Oregon's beaches for public access, the Land Conservation and Development Commission, which baked land use planning into our way of life—as well as more personal insights into pioneering Oregon luminaries like Tom McCall, L.B. Day, Betty Roberts and Gretchen Kafoury.

The Only Woman in the Room: The Norma Paulus Story by Norma Paulus with Gail Wells and Pat McCord Amacher, startled me on many levels. As a native Oregonian who lived through the years covered by this biography and knew many of the names and issues described in it, I was fascinated to learn of the behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing involved in some of the biggest headlines—think the bottle bill, saving Oregon's beaches for public access, the Land Conservation and Development Commission, which baked land use planning into our way of life—as well as more personal insights into pioneering Oregon luminaries like Tom McCall, L.B. Day, Betty Roberts and Gretchen Kafoury.

The book recounts that Paulus, a representative of a more moderate Republican party than we know today, and many in her party were pro-environment, advocated for women's rights—Oregon ratified the Equal Rights Amendment not once, but twice—and helped give Oregon its (now sadly diminished) reputation as a bastion of progressive government.

As the first woman elected to statewide office, as Secretary of State in 1976, Paulus was a practical yet visionary leader in her public career, though her dream to become Oregon's first woman governor was dashed in a bitter (if close) loss to Neil Goldschmidt in 1986; Barbara Roberts was to earn that distinction in 1991.

A chronicle of Oregon politics during a critical time in our history as well as the remarkable personal story of a woman's growth from humble beginnings to acclaim on a national stage, this is good read for longtime and newer Oregonians alike.

In case you're counting, the other (half) book, which I'd started before we arrived at the cabin and finished soon after, was the excellent Raw Material: Working Wool in the West by Stephany Wilkes, reviewed here.