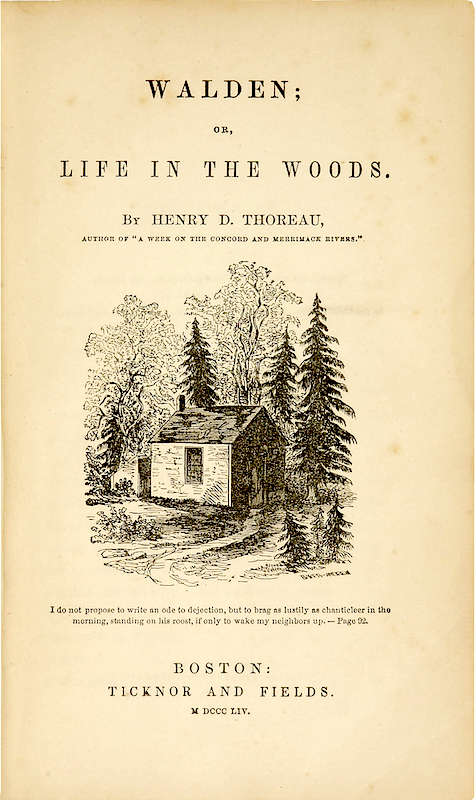

Book Report: The Man Who Ate Too Much

“The fresh butter has another taste,” James would tell Jane Nickerson about trying to approximate Parisian ingredients in New York [for his book Paris Cuisine, published in 1952]. “Vegetables and fruits, because they are grown in different soil and travel shorter distances, may be fuller flavored. The small, small peas the French so like are not offered in our markets.” He knew these dishes at the source. The transformation that happened to them on another continent—the degree to which even nominally identical ingredients, carrots or salt or wheat flour, changed because of where and how they grew or formed—was a revelation to James. It was the beginning of the winemaker’s notion of terroir extending to more than wines—indeed, to all the things the land produces in a defined region.

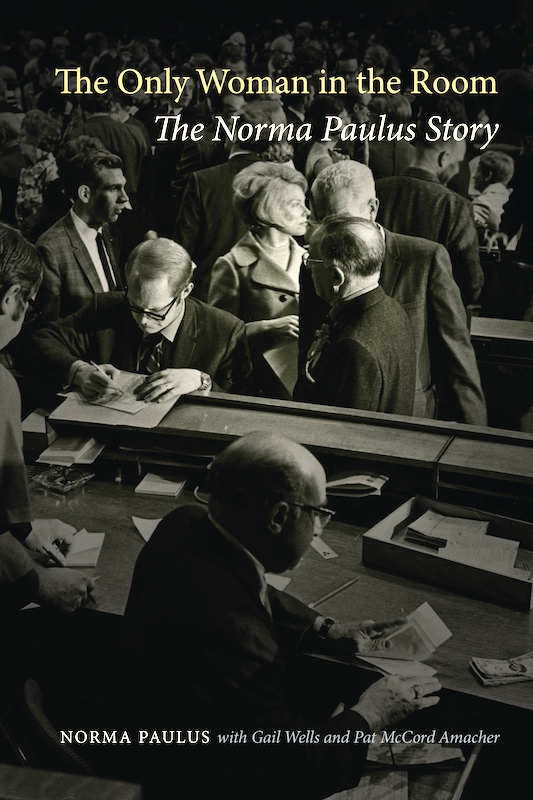

- John Birdsall, "The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard"

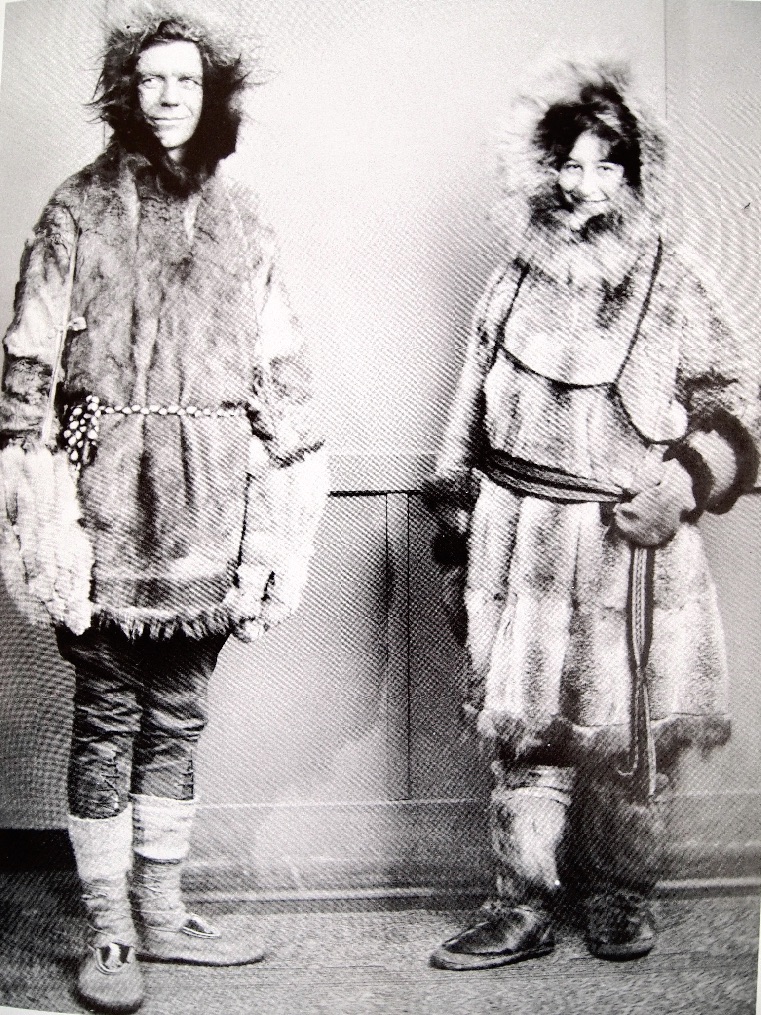

James Beard is, without a doubt, one of the most well-known Oregonians our state has ever produced. His nearly century-long life—from his birth in 1903 to his death in 1985—evangelizing the pleasures of eating and cooking with the freshest of what is grown and produced wherever he found himself is without precedent. Yet his chameleon-like ability to both stand for the enjoyment of flavorful food as well as surf the onslaught of the 20th Century's industrial, mass-produced trends like frozen food and canned goods, while still cranking out massive numbers of books, columns, and live appearances in order to earn a living, is truly astonishing.

This while keeping his queer life completely shrouded from the view of all but the closest of his intimates.

This while keeping his queer life completely shrouded from the view of all but the closest of his intimates.

In "The Man Who Ate Too Much: The Life of James Beard," Birdsall has written a sprawling biography of Beard's life from his birth to Elizabeth and John Beard in Portland that details his parents' unambiguously antagonistic relationship—his mother, an independent businesswoman before her marriage, had at least one longterm affair with a prominent actress while relegating her husband to his own room in the back of their house. For his part, John kept a mistress with whom he had at least one child. James grew up in the lonely netherworld between them, cared for in his early life by their Chinese cook, Jue Let.

This readable, intensively researched book—Birdsall's research notes and sources run 60 pages—initially covers much the same territory as Robert Clark's biography of Beard from 1993, but includes voluminous detail about his private life as an internationally famous, but closeted, queer man (as Birdsall terms it). Equally fascinating is the story of how queerness, and the (mostly) male culinary stars of the mid-to-late 20th Century came to define, as epitomized by Beard himself, the food and cooking most of us call American cuisine.

(This is not surprising, since Birdsall was the author of an article on that topic for the now-shuttered Lucky Peach magazine, titled "America, Your Food Is So Gay," which won him a James Beard Foundation Award in 2014.)

Birdsall doesn't shy away from Beard's foibles and failings in this book, including his tendency to take credit for recipes developed by others, plagiarize his own recipes published elsewhere, as well as take advantage of the people who shaped his books and columns—including uncredited editorial help from Isabel Callvert, Helen and Philip Brown, and many others.

It is truly a fascinating read, one that I'd recommend to those interested not just in Beard and the food history of the 20th Century, but also to anyone who wants to learn more about queer culture and how it survived in the pockets and shadows of that period.

Birdsall writes about the gala tribute, headlined by 14 of the country's best-known chefs, held in New York City after Beard’s death in 1985 at the age of 82:

“James—the Dean of American Gastronomy (an upgrade from “Cookery,” his epithet of thirty years)—was part of the previous generation of American food masters. Along with Julia Child and Craig Claiborne—both still very much alive—James was the ultimate amateur cook, dedicated to home cooking. The new generation of American culinary authorities were chefs, each exciting and glamorous in ways James, Julia, and Claiborne never were.”

Get the recipe for my version of James Beards' classic macaroni and cheese casserole adapted from his Beard on Pasta book.

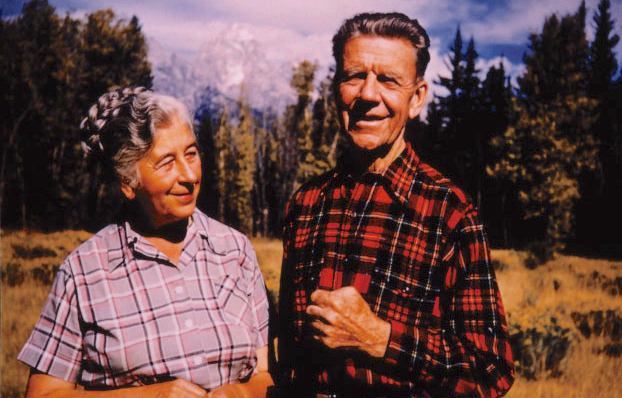

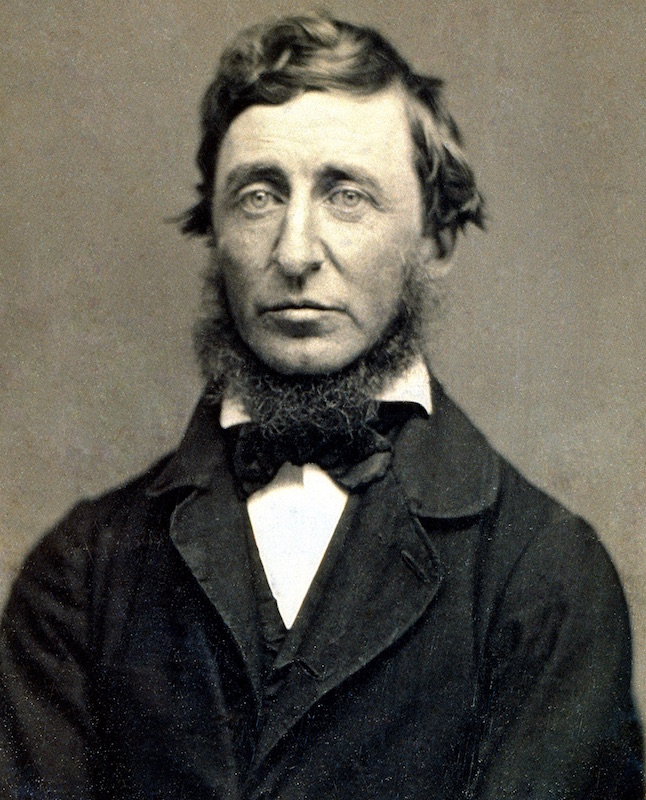

Top photo of James Beard (and his famous pineapple wallpaper) from the book.

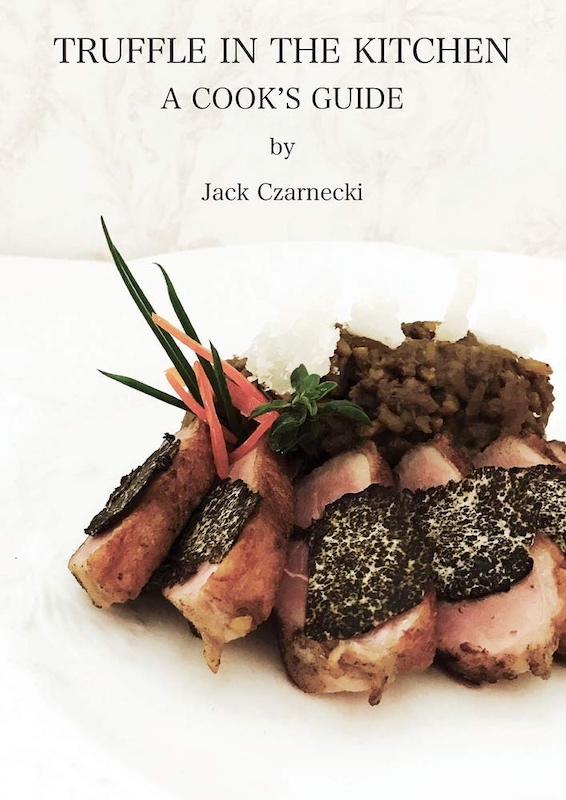

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed  His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle.

His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle. No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven

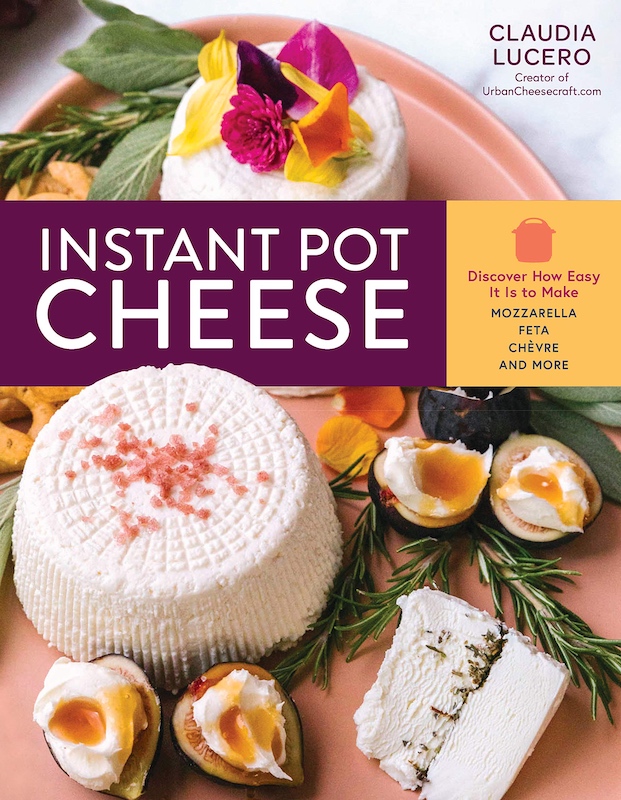

No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven  The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking.

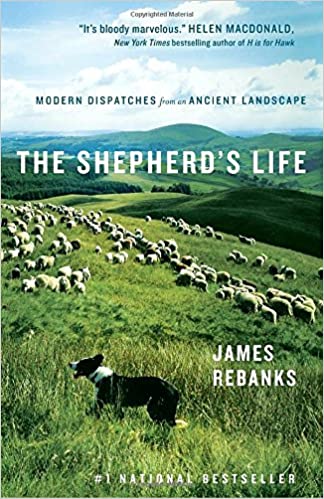

The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking. I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his

I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his  Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

For something completely different,

For something completely different,