Guest Essay: Patience

In previous posts I've written about my love of cookbooks and my admiration-verging-on-adoration for the inimitable Julia Child. When my friend Mary Bartlett—chef, author, bon vivant and part-time resident of Portland and Paris where she co-hosted the legendary Sunday Suppers held at Jim Haynes atelier in the City of Light—posted the following essay on her Facebook page, I immediately asked if I could repost it here. Mary generously acceded.

"Beautiful!"

"Delicious!"

"Marvelous."

"Go very lightly on the brown sugar."

"My favorite!"

(Scribblings in my cookbook.)

Boston. 1969. An aunt gives me Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child, Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle. I had just returned from a year in France as a college student and felt passionate about French food. This book, a best-ever gift, battle-worn, stained, and shredded, remains precious to me over half a century later.

First published by Knopf in 1961, Mastering the Art of French Cooking introduced French cuisine to Americans. In the foreword, Julia (and she was the principal author) says this:

"This is a book for the servantless American cook who can be unconcerned on occasion with budgets, waistlines, time schedules, children's meals, the parent-chauffeur-den mother syndrome, or anything else which might interfere with the enjoyment of producing something wonderful to eat."

For many Americans, French cooking was perceived to be overly rich, heavy, too fancy and full of weird things (like a lot of liver). Julia's book explained that a typical French menu was composed of several courses. People didn't have three helpings of mashed potatoes or a two-pound steak. They ate smaller quantities with plenty of variety.

Over time, as cooking shows proliferated and a quick internet search delivered any recipe, cookbooks in general have become passé. While Mastering the Art of French Cooking has sold over 1.5 million copies, it's hard to imagine most people taking the time to read and study it now. But Julia Child herself continues to play a large part—through television shows and series—in American popular culture.

Over time, as cooking shows proliferated and a quick internet search delivered any recipe, cookbooks in general have become passé. While Mastering the Art of French Cooking has sold over 1.5 million copies, it's hard to imagine most people taking the time to read and study it now. But Julia Child herself continues to play a large part—through television shows and series—in American popular culture.

The meals prepared by the French family I lived with in 1968 were typical: very small breakfasts (bread and coffee), lunch with several courses including cheese and dessert, and a light dinner (often soup, bread and salad). Children had gouter or a snack, often an éclair or a pain au chocolat after school, but otherwise there was no snacking. The main meal varied between lunch and dinner depending on work and school schedules but a full Sunday lunch was customary and often included grandparents.

One funny memory: In my French family's house, there was always a large saucepan simmering on the back of the stove which contained various scraps and bones. When I asked, I was told "C'est la soupe du chien." It was the dog's soup and that is what the dog was fed. Nothing was wasted.

Reading Mastering the Art requires patience and plenty of time. There are no shortcuts and the recipes are followed by copious recommendations for accompaniments. As an example, the chapter on leg of lamb is fifteen pages long and has seven suggestions for traditional vegetable garnitures: Bruxelloise, Châtelaine, Clamart, Florian, Judic, Provençale and Viroflay. Artichoke hearts, Brussels sprouts, braised lettuce, stuffed mushrooms, or whole baked tomatoes were just some of these and each garniture referenced specific recipes and their page numbers.

I made the roast leg of lamb on March 28th, 1969, according to my note in the margin along with the following comment: "Cook a bit longer than it says—unless it is really room temp when put in oven."

My enthusiasm for this cookbook and my dedication to learning the techniques hit a big snag, however. I was unprepared for the omelette.

This is the cheery introduction to the eleven pages of treatise and recipes in the omelette chapter:

"A good French omelette is a smooth, gently swelling golden oval that is tender and creamy inside. And as it takes less than half a minute to make, it is ideal for a quick meal."

Less than half a minute? Between wrestling with my pan, its handle, the shaking, the lifting and finally slapping an egg mixture that was neither smooth nor gently swollen onto a plate, my omelette was a disaster.

I tried more than once and while I should have taken to heart her cautionary advice—"…before you even start to make one you must read, remember, and visualize the directions from beginning to end, and practice the movements"—I ended up frustrated and seething.

Then I remembered: Julia lived in Cambridge! Right across the river! I raced to the telephone book (yes, children, that's what we had in those days) and sure enough, there was a listing. I telephoned and Paul Child answered. Julia was away for the afternoon but perhaps he could help.

"Less than half a minute to make an omelette?" I sputtered. "It's impossible."

"Now, now," he said gently. "It's patience. That's all you need."

"Really?" I was unconvinced."Yes," Paul said firmly, "Keep making omelettes and you'll be making them in less than 30 seconds."

Patience won out. And I learned it's not a clock race, it's producing that gently swollen, tender and creamy eggy marvel.

Thank you, Paul Child.

Get a copy of Mary's Throw a Great Party that recounts menus and recipes from those fabulous Sunday dinners in Paris with Jim Haynes.

Photo by Mary Bartlett of her well-loved copy of Julia's classic Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

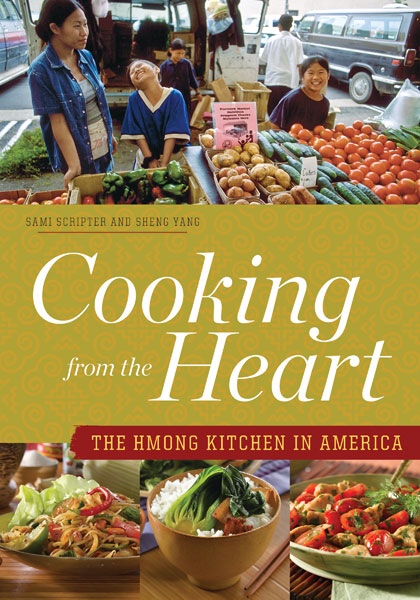

But to tell the story of the book, we need to go back to 1980. That's when Sami Scripter, the coordinator of the talented and gifted program at Rigler Elementary School in Portland, met Sheng Yang, a young Hmong (pron. "mong") immigrant, in her English as a Second Language class. Scripter's desk was in one corner of the room, and she was taken with the inquisitive and self-possessed 11-year-old.

But to tell the story of the book, we need to go back to 1980. That's when Sami Scripter, the coordinator of the talented and gifted program at Rigler Elementary School in Portland, met Sheng Yang, a young Hmong (pron. "mong") immigrant, in her English as a Second Language class. Scripter's desk was in one corner of the room, and she was taken with the inquisitive and self-possessed 11-year-old.

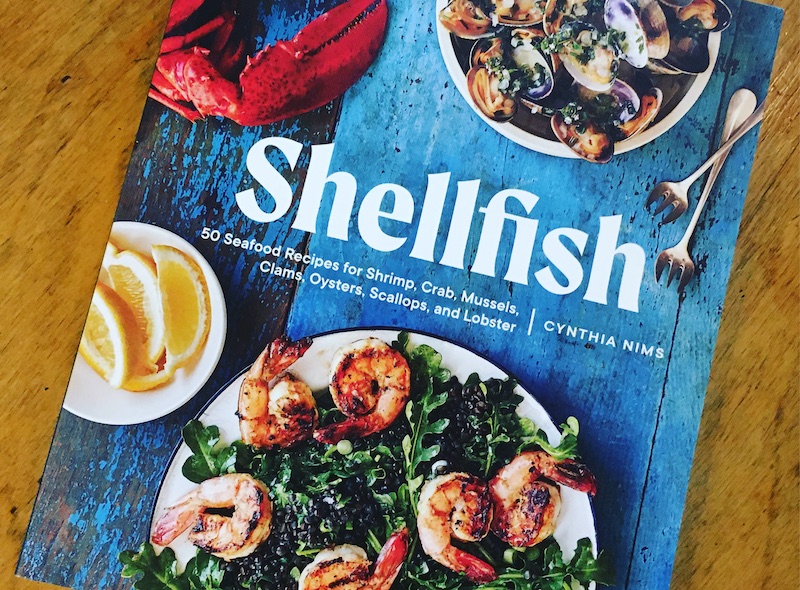

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including  You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book,

You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book,

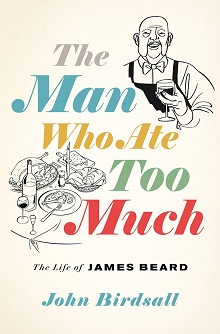

This while keeping his queer life completely shrouded from the view of all but the closest of his intimates.

This while keeping his queer life completely shrouded from the view of all but the closest of his intimates.

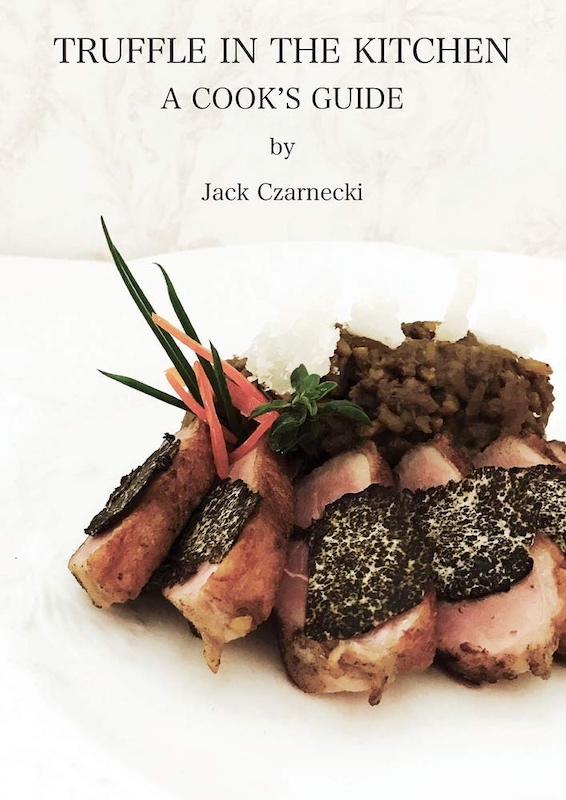

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed  His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle.

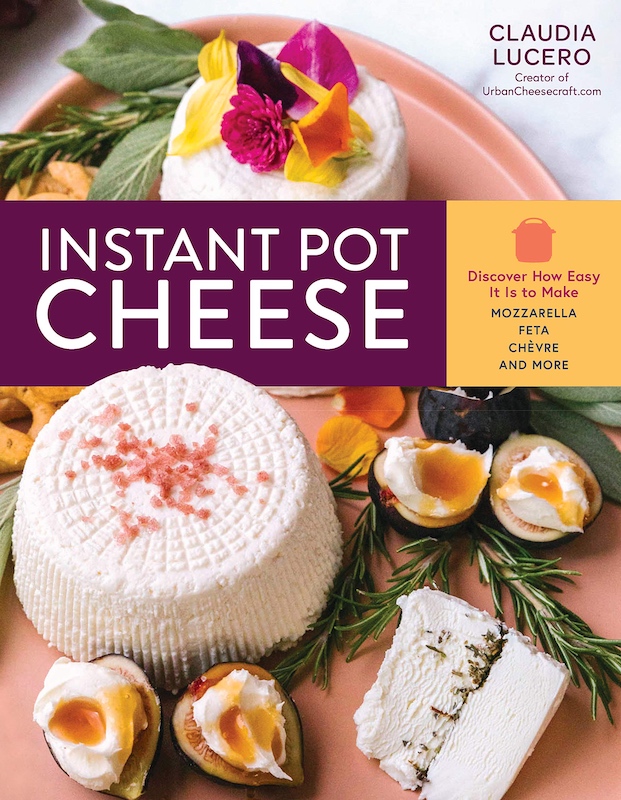

His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle. No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven

No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven  The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking.

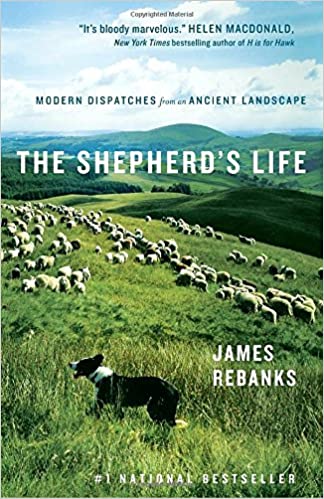

The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking. I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his

I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his  Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,