Guest Post: Corn and Beans

Josh Volk is the farmer at Cully Neighborhood Farm. This essay originally appeared on the farm's blog. You can read a profile of Josh and his work.

We grew out eight of our dry bean varieties this summer and between the good weather and giving them a head start by transplanting, for the first time we actually got them in earlier than ever. So I figured it was time to make a post with more description of each variety.

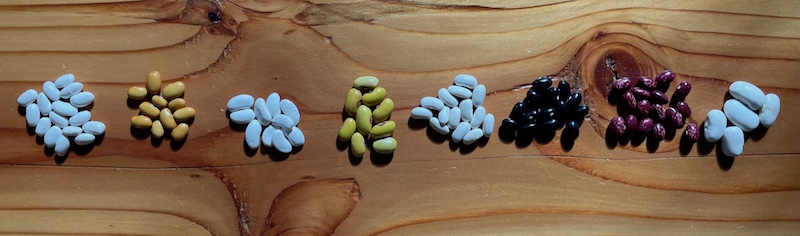

I’ll list them in order from left to right in the photo below. At the bottom of the post I’ll describe the two corn varieties that we grew with the beans (and have been growing for many years now).

Dry Beans

If you’ve only ever had canned beans, or bought dry beans from the bulk section, these are a completely different experience. They cook easily and evenly and have an extra layer of flavor. In general these all have delicate skins and cook well by soaking overnight, then bringing to a boil and gently simmering for as little as 20 minutes, although as they get older they’ll take a bit longer, maybe 45 minutes to an hour. Add salt and other seasoning to taste, generally about one to two teaspoons of salt per pound. Alternatively, I really like to use the residual heat from baking in my oven to cook the beans gently by putting them in a covered, heatproof container and baking them instead of cooking them on the stove top—same directions otherwise. Be sure to save the cooking liquid, which is delicious.

Nico Cannellini. This is the one bean I haven’t cooked with much! They were brought to me as a gift from a farmer in Tuscany a few years ago and I’ve been slowly increasing the amount I’ve been growing. This is the same farmer who I got the polenta corn from and I don’t know if there’s really a variety name, but I’ve just named the beans after his farm, Agricola Biologica Nico. On a side note, the Pescia and Piattella white beans we grow [see descriptions below] are also cannellini types, but each is distinct in size and shape, with subtle flavor differences.

Swedish Brown. I’ve been growing this bean for so long I don’t even remember where I got it or why. I’ve probably been growing it for 25 years now and I just really like the flavor. It’s a bit like a pinto bean, but so much more flavorful.

Piattella. I got this one from a grower in Italy who also uses corn for trellising. It’s a Slow Food Ark variety [link here] and you might try to find it from the Italian growers if you really like it and [in that way] support their efforts to keep it growing in its traditional areas.

If you’ve only ever had canned beans, or dry beans

from the bulk section, these are a completely different experience.

Yellow Forest (Giele Wâldbeantsje). This is another Slow Food Ark variety [link here]. It’s from the Netherlands and does pretty well here. Flavor wise it’s similar to the Swedish Brown beans but it’s much larger. As these beans age in storage their color changes from light yellow to a darker yellow, and there’s some variation even when they are newly dried.

Pescia (Sorana). A great little white bean, very tender and tasty. Lane Selman and I brought this back from Italy by request for Uprising Seeds in 2014 and they shared seeds from their first grow out with me the following year. I’ve been growing it since then and it’s a favorite for its great flavor and early drying on the vine. It’s a Slow Food Ark and Presidium variety under the name Sorana and you might try to find it from the Italian growers if you really like it and [in that way] support their efforts to keep it growing in its traditional areas. Uprising calls it Pescia, after the area where it is grown, as the Sorana name is protected and should only be used by growers in the protected area.

Tolosaka. This is my name for the tolosa black bean, which I’ve been growing since 2007. This is a beautiful, large, deeply black bean that is from the Basque region of Spain. Look it up, apparently it’s famous [Uprising Seeds offers it]. I just know it’s delicious and one of my favorites.

Red Forest (Reade Krobbe). Another Dutch Slow Food Ark variety [link here]. As with all of these beans I just like eating these by themselves, but they’re also very good in soups as they hold their shape well. I’ve also made red bean paste with them for sweets.

White Runner (Katherine’s). All of the other beans we grow are Phaseolus vulgaris, but these are Phaseolus coccineus. They are related to the more common Scarlet Runner beans but have white flowers and beans. As with all runner beans I’ve had they are very large with delicious meaty interiors and incredibly delicate skins when cooked. My friend Katherine Deumling was my original source for this variety and a neighbor of her family in Salem was the grower. I don’t remember the variety name, just that I got them from her and that they grow better for me than the better known Corona White Runner bean—which is even larger, but doesn’t ripen well here (even these runner beans are a little marginal and tend to mature a bit late).

Corn

Dakota Black Popcorn. pops bright white and with great fresh popcorn flavor, not at all like the big stale stuff you get in most bulk bins. If you have a grinder that will grind hard corn it makes a good addition to pancakes and bread (popcorn is very hard and many grinders aren’t strong enough to grind it).

Otto File Polenta Corn. A number of years ago I was in Italy and visited a wonderful little biodynamic market farm in Lucca. The farmer gave me an ear of his golden polenta corn (otto file, meaning eight rows in Italian, because there are eight rows of kernels on the slender cobs). I ended up planting it in my garden and it made amazing polenta—tons of corn flavor, beautiful golden color, slightly sweet—so I grew more. We use a relatively inexpensive Corona hand cranked grist mill to grind it into polenta, but there are many other options out there (these mills will also grind popcorn). It can also be cooked whole, but it does not make good nixtamal in my opinion—very gummy.

Top photo of a simple bean, green cabbage and bacon soup with carrots, onions and garlic.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering. Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.

Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.