Hood Strawberry Sorbet Sets a High Bar for Summer

The appearance of Hood strawberries marks the official beginning of summer in Oregon. While other strawberries may appear sooner, it's the Hoods that people await with bated breath, pestering farmers and greengrocers with the question of, "When???"

And no other strawberry will do for a true Oregon strawberry jam, according to devotées. The section on Hood strawberries at a website dedicated to these signature gems notes that Hoods are only available in a short window of two to three weeks at the very beginning of strawberry season.

Fans will nod in agreement upon reading that Hoods are known for their high sugar content and deep red color throughout and, when ripe, they are much softer in texture than other varieties. And, as anyone who has bought a flat of Hoods and put off using them until the next day knows, the description solemnly notes that they "need to be eaten fresh or used in jams or baking within hours of being picked."

Discovering a flat of mushy brown berries the next day is, as the Mavericks sang in 1994, a crying shame.

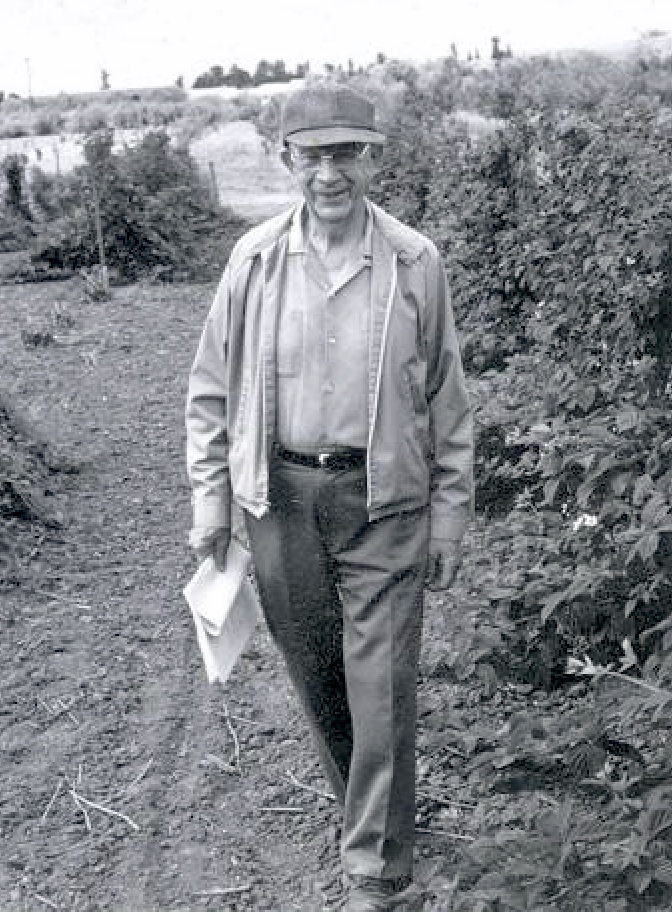

Hoods were officially released to fruit growers and the nursery industry on April 16, 1965, a cross between a cultivar called "US-Oreg 2315" and Puget Beauty. It was grown and selected by legendary plant breeder George F. Waldo, who was said to have transformed Oregon's berry industry with the introduction of the Hood strawberry as well as the Marionberry.

When I brought home two pints of freshly picked Hoods from Greenville Farms at the Hollywood Farmers Market, Dave, prescient as always, immediately claimed them for a batch of his justly famous strawberry sorbet. The bar for summer has been set!

Strawberry Sorbet

Adapted from Sheila Lukins

2 pints fresh strawberries

1 1/4 c. simple syrup (recipe below)

2 Tbsp. orange juice

To make the simple syrup, in a medium saucepan combine two cups each of water and granulated sugar. Heat until just boiling, stirring occasionally. Cool.

Purée the strawberries with 1/4 cup of the simple syrup in a food processor until smooth. While the seeds of the Hood strawberry are quite small and fine to use at this point, if using other berries you may want to strain the pulp through a fine mesh sieve to get a smoother purée.

Stir in the remaining syrup and the orange juice. Transfer to an ice cream machine and freeze according to the manufacturer's instructions.

I got to talk to farmers like Betsy Harrison of

I got to talk to farmers like Betsy Harrison of

When it's all bubbly and ready to go to work, you'll need to save out a bit for your next project down the road, then take out however much you need for the job at hand. That leaves about half of that ready-to-rock starter sitting there staring at you.

When it's all bubbly and ready to go to work, you'll need to save out a bit for your next project down the road, then take out however much you need for the job at hand. That leaves about half of that ready-to-rock starter sitting there staring at you. Fortunately Dave is always on the prowl for recipes using sourdough discard, and is a dedicated fan of the

Fortunately Dave is always on the prowl for recipes using sourdough discard, and is a dedicated fan of the

I love cornmeal ground from organic flint corn with its rustic flecks of red, orange and yellow, and recently I've found a substitute for my beloved Ayers Creek Farm Roy's Calais Flint. Called Floriani Red Flint and grown by Fritz Durst of Tule Farms in Capay, California, it's a rich organic corn flour ground in Junction City by Camas Country Mill.

I love cornmeal ground from organic flint corn with its rustic flecks of red, orange and yellow, and recently I've found a substitute for my beloved Ayers Creek Farm Roy's Calais Flint. Called Floriani Red Flint and grown by Fritz Durst of Tule Farms in Capay, California, it's a rich organic corn flour ground in Junction City by Camas Country Mill.

The

The  The

The  The bill would have expanded the venues where farms under the micro-dairy exemptions could sell raw milk, to include delivery, at farmers' markets and farm stands if they label the raw milk. The bill would also have legalized the retail sale of raw cow milk and cow milk products to retail stores including butter, cheese and ice cream.

The bill would have expanded the venues where farms under the micro-dairy exemptions could sell raw milk, to include delivery, at farmers' markets and farm stands if they label the raw milk. The bill would also have legalized the retail sale of raw cow milk and cow milk products to retail stores including butter, cheese and ice cream.