Cynthia Nims is a prolific author. The list of books she's written would take up most of the space in the cupboard I've dedicated to my whole cookbook collection—don't ask where I keep the stacks of other cookbooks that have yet to be shelved. In total, her work is a comprehensive overview of the bounty we Northwesterners enjoy, a celebration of the seasonal riches harvested from our rivers, our forests and our oceans.

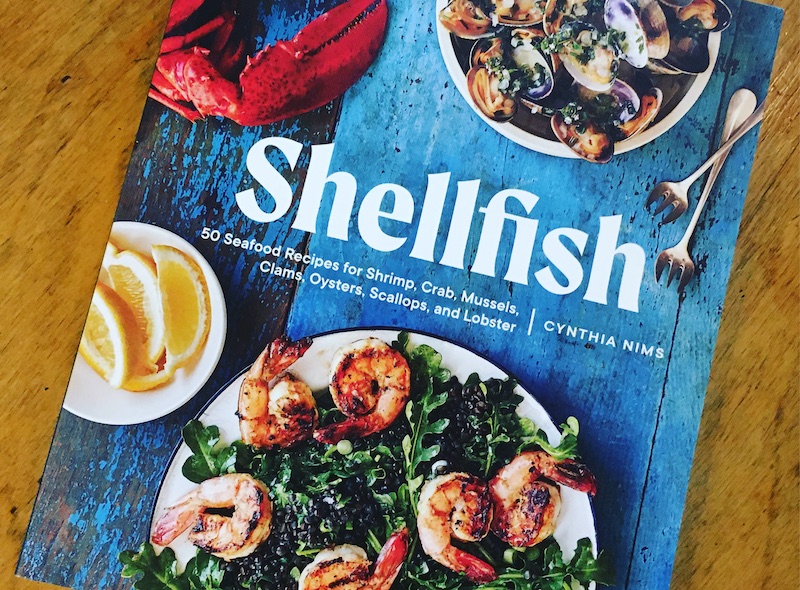

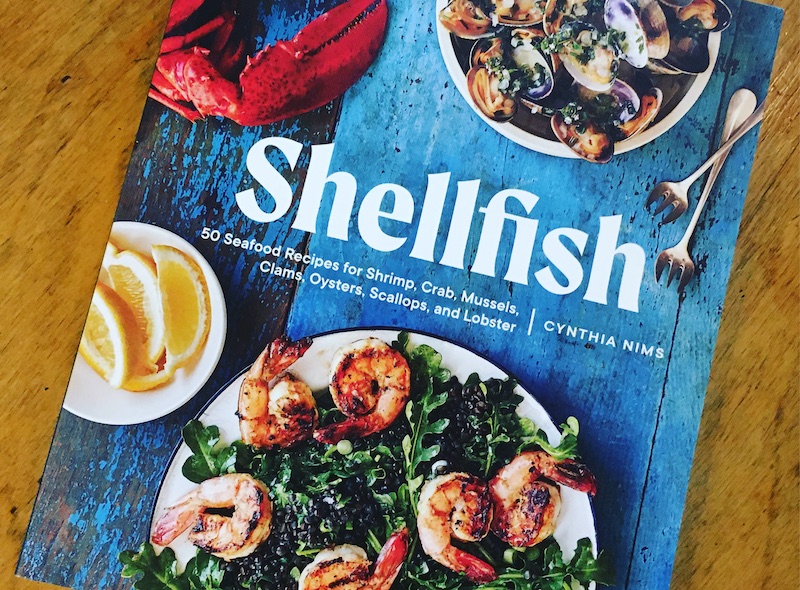

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including Crab, Oysters and her latest, Shellfish. Then there are the Northwest Cookbooks e-book series (Crab, Salmon, Wild Mushrooms, Appetizers, Breakfast, Main Courses, Soups, and Salads & Sandwiches); plus the dear-to-her-heart Salty Snacks and Gourmet Game Night. Personal note: I've been angling to visit Nims in Seattle to get a tour (and maybe a taste) at her period-perfect Lava Lounge where she spins recordings—only vinyl, my dear, please—serves cocktails and runs a board game emporium for friends.

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including Crab, Oysters and her latest, Shellfish. Then there are the Northwest Cookbooks e-book series (Crab, Salmon, Wild Mushrooms, Appetizers, Breakfast, Main Courses, Soups, and Salads & Sandwiches); plus the dear-to-her-heart Salty Snacks and Gourmet Game Night. Personal note: I've been angling to visit Nims in Seattle to get a tour (and maybe a taste) at her period-perfect Lava Lounge where she spins recordings—only vinyl, my dear, please—serves cocktails and runs a board game emporium for friends.

Like many of us in the food writing world, it wasn't her automatic career choice:

"Cooking has been under my skin for as long as I can remember, inspired by the sheer pleasure of cooking with my mom and big sister. I mastered the canned-pear-half-with-cottage-cheese-tail bunny salad, subscribed to Seventeen magazine for the recipes, and had my high school third-year French class over for dinner, which included a soupe à l’oignon that began with beef stock made a couple days prior."

A math degree with an eye toward becoming an engineer was scuttled after Nims attended the stagiaire program at La Varenne, which culminated in receiving the school’s Grand Diplôme d’Etudes Culinaires. She's cooked for Julia Child and the Flying Karamzov Brothers, beginning her immersion in the subject of seafood, appropriately, at Simply Seafood magazine. Nims has taught classes and co-authored, edited and contributed to dozens of publications, including the highly lauded series Modernist Cuisine.

You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book, Shellfish: 50 Seafood Recipes for Shrimp, Crab, Mussels, Clams, Oysters, Scallops, and Lobster, to Flying Fish on Saturday, July 23rd, from 1 to 3 p.m. Nims will be in the Chef Shack alongside Chef Trever Gilbert, who's featuring the book's Harissa Roasted Shrimp, Carrots and Radishes. Then she'll be demo-ing a couple of recipes at Vivienne Kitchen and Pantry—in their Secret Bar, no less—on Sunday, July 24th, from 3 to 5 p.m.

You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book, Shellfish: 50 Seafood Recipes for Shrimp, Crab, Mussels, Clams, Oysters, Scallops, and Lobster, to Flying Fish on Saturday, July 23rd, from 1 to 3 p.m. Nims will be in the Chef Shack alongside Chef Trever Gilbert, who's featuring the book's Harissa Roasted Shrimp, Carrots and Radishes. Then she'll be demo-ing a couple of recipes at Vivienne Kitchen and Pantry—in their Secret Bar, no less—on Sunday, July 24th, from 3 to 5 p.m.

If you want to get a taste of just how fabulous this book is, try her simple (and seriously divine) Grilled Clam Pouches with Bay Leaf and Butter (photo above right). I made them just last night and after his first bite, Dave said, "This is going on the list for camping."

Grilled Clam Pouches with Bay Leaf and Butter

Fresh bay leaves really stand out in the preparation; dried leaves won't offer as much fragrant flavor. A rosemary or thyme sprig in each packet, or a couple of fresh sage leaves, can be used in place of fresh bay. And you can't go wrong with just buttter and clams on the grill, either. I use 12-inch wide aluminum foil; you can use larger and/or heavy duty foil if you like.

The packets make a good serving vessel perched on a plate for casual dining. You can instead transfer the clams and buttery cooking juices to shallow bowls. These lighter portions are ideal as an appetizer, followed perhaps by other items destined for the grill while it's hot.

Makes 4 servings.

2 lbs. small to medium live hard-shell clams, well-rinsed

4 Tbsp. unsalted butter, divided

8 fresh bay leaves, divided

Sliced baguette or other bread, for serving

Preheat an outdoor grill for medium-high direct heat.

Cut 8 pieces aluminum foil about 12 inches long and arrange them on the counter stacked in pairs for making 4 packets.

Put 1 tablespoon of butter in the center of each foil packet. Fold or tear each bay leaf in half which helps release its aromattic character, and put 2 leaves on or alongside the butter for each packet. Divide the clams evenly among the pouches, mounding them on top of the butter and bay and leaving a few inches of foil all around.

Draw the four corners of the foil up over the clams to meet in the center and crimp together along the edges, where the sides of the foil meet, so the packet is well-sealed. The goal is to create pouches that will hold in the steam for cooking and preserve the flavorful cooking juices that result.

Set the foil packets on the grill, cover, and cook for about 10 to 12 minutes for small clams, 12 to 15 minutes for medium. Partly open a packet to see if all the clams have opened, being careful to avoid the escaping steam; if not, reseal and cook for another 2 to 3 minutes.

Set each pouch on an individual plate and fold down the foil edges, creating a rustic bowl of sorts to hold the flavorful cooking liquids. Or carefully transfer the contents to shallow bowls. Serve right away, with bread alongside, discarding any clams that did not open.

NOTE: This recipe works well in the oven, too. Preheat the oven to 475 degrees F. Use a broad, shallow vessel, such as a large cast-iron skillet or a 12-inch gratin dish or similar baking dish. Add the butter pieces and bay leaves to the dish and put in the oven until the butter has melted. Take the dish from the oven, add the clams in a relatively even layer, and return the dish to the oven. Roast until all, or mostly all, of the clams have opened, 12 to 15 minutes. Spoon the clams into individual shallow bowls, discarding any that did not open, then carefully pour the buttery cooking liquids over the top.

Nine breweries across the state are making new beers with Oregon-sourced ingredients and supporting the work of OAT to permanently protect Oregon’s bountiful farm and ranch lands from development. Beginning October 12, participating breweries will release the beers on draft, with six of the nine beers packaged in limited-edition Cheers to the Land 16-ounce, 4-pack cans.

Nine breweries across the state are making new beers with Oregon-sourced ingredients and supporting the work of OAT to permanently protect Oregon’s bountiful farm and ranch lands from development. Beginning October 12, participating breweries will release the beers on draft, with six of the nine beers packaged in limited-edition Cheers to the Land 16-ounce, 4-pack cans. As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting special events at each brewery during October, as well as Cheers to the Land Tap Takeovers, with all nine beers at Loyal Legion in both Portland and Beaverton on Oct. 14 and 15, respectively. And it's no token effort on the part of the brewers: Each participating brewery is supporting Oregon farmers in the creation of their beers, and also supports the work of OAT through a donation of the beer’s proceeds.

As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting special events at each brewery during October, as well as Cheers to the Land Tap Takeovers, with all nine beers at Loyal Legion in both Portland and Beaverton on Oct. 14 and 15, respectively. And it's no token effort on the part of the brewers: Each participating brewery is supporting Oregon farmers in the creation of their beers, and also supports the work of OAT through a donation of the beer’s proceeds.

There are many kinds of meals. There are those that simply feed you, those that feed your soul, and those that are so memorable that they rate right up there with the best experiences of your life. A meal at Joel Robuchon’s in Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel is such an experience. Robuchon was named “Chef of the Century” by the Gault Millau in 1989 and had 32 Michelin stars, the most of any chef, at his time of death from pancreatic cancer in 2018.

There are many kinds of meals. There are those that simply feed you, those that feed your soul, and those that are so memorable that they rate right up there with the best experiences of your life. A meal at Joel Robuchon’s in Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel is such an experience. Robuchon was named “Chef of the Century” by the Gault Millau in 1989 and had 32 Michelin stars, the most of any chef, at his time of death from pancreatic cancer in 2018.  So it is with great enthusiasm that Ginger embraces the hot new trend shepherded to fame by TikTok creator Justine Doiron: The Butter Board. Most of you are familiar with charcuterie boards—tasty combinations of meats and cheeses, along with complementary accompaniments such as fruits and nuts that make for great snacking and conversation when served among friends and family. Well, a Butter Board is a similar concept, only the main attraction is the excellent quality butter that has been creatively enhanced and surrounded by pieces of bread and crackers.

So it is with great enthusiasm that Ginger embraces the hot new trend shepherded to fame by TikTok creator Justine Doiron: The Butter Board. Most of you are familiar with charcuterie boards—tasty combinations of meats and cheeses, along with complementary accompaniments such as fruits and nuts that make for great snacking and conversation when served among friends and family. Well, a Butter Board is a similar concept, only the main attraction is the excellent quality butter that has been creatively enhanced and surrounded by pieces of bread and crackers. The thing that is so wonderful about this idea is that it is relatively simple to prepare, and you can get as creative as you want with the combinations of ingredients. First, you start with fabulous butter. Do not skimp here! Here at the Beaverton Farmers Market, we are lucky to have the gorgeous butter made by our friends at

The thing that is so wonderful about this idea is that it is relatively simple to prepare, and you can get as creative as you want with the combinations of ingredients. First, you start with fabulous butter. Do not skimp here! Here at the Beaverton Farmers Market, we are lucky to have the gorgeous butter made by our friends at

Lately I've found some mighty meaty collars, almost like a fish steak with wings, at

Lately I've found some mighty meaty collars, almost like a fish steak with wings, at

It's made using shiso leaves, halfway between a leafy green and an herb that the New York Times described as "a mysterious, bright taste that reminds people of mint, basil, tarragon, cilantro, cinnamon, anise or the smell of a mountain meadow after a rainstorm." (Ooooookay…?) I'd say it's flavor is on the same spectrum as cilantro: definitely pungent, with a slightly minty twang. Shiso is, for me, a little strong to use in a salad, for instance, but the process of fermentation and the other ingredients in the brine—soy, ginger, garlic and the Korean ground peppers called gochugaru—seem to tame its somewhat, shall we say, overpowering personality.

It's made using shiso leaves, halfway between a leafy green and an herb that the New York Times described as "a mysterious, bright taste that reminds people of mint, basil, tarragon, cilantro, cinnamon, anise or the smell of a mountain meadow after a rainstorm." (Ooooookay…?) I'd say it's flavor is on the same spectrum as cilantro: definitely pungent, with a slightly minty twang. Shiso is, for me, a little strong to use in a salad, for instance, but the process of fermentation and the other ingredients in the brine—soy, ginger, garlic and the Korean ground peppers called gochugaru—seem to tame its somewhat, shall we say, overpowering personality. The recipe is adapted from a book I absolutely love,

The recipe is adapted from a book I absolutely love,

Among its many attributes, a medium peach is a mere 37 calories and is high in vitamins A, B, and C. Because a fully ripe peach is delicate and easily bruised, you will often find them sold just “under-ripe.” To fully ripen your fruit, place them on the counter in a brown paper sack, folded closed, for two or three days. (Do not try this in a plastic bag. As the fruit respires, it gives off moisture which will collect on the plastic bag and cause the fruit to rot.) The ripe fruit will be soft and fragrant. Refrigerate them at this point.

Among its many attributes, a medium peach is a mere 37 calories and is high in vitamins A, B, and C. Because a fully ripe peach is delicate and easily bruised, you will often find them sold just “under-ripe.” To fully ripen your fruit, place them on the counter in a brown paper sack, folded closed, for two or three days. (Do not try this in a plastic bag. As the fruit respires, it gives off moisture which will collect on the plastic bag and cause the fruit to rot.) The ripe fruit will be soft and fragrant. Refrigerate them at this point.  Like the plum and the apricot, peaches are members of the rose family (Rosaceae), distinguished by their velvety skin. If the peach fuzz bothers you, try rubbing the fruit with a terry handtowel after washing, it will diminish the feel of the fuzz on your mouth. Of course, you could also choose to purchase nectarines instead if the fuzzy skin bothers you.

Like the plum and the apricot, peaches are members of the rose family (Rosaceae), distinguished by their velvety skin. If the peach fuzz bothers you, try rubbing the fruit with a terry handtowel after washing, it will diminish the feel of the fuzz on your mouth. Of course, you could also choose to purchase nectarines instead if the fuzzy skin bothers you.

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including

There are Nims' recent single-subject seafood books, including  You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book,

You can meet this culinary wonder woman this weekend at two events in Portland where she's bringing her new book,