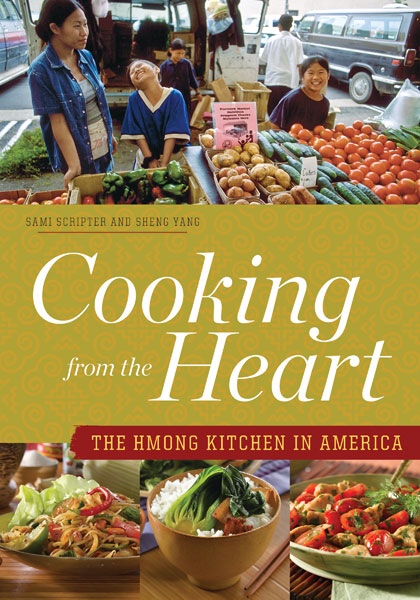

Book Review: Cooking from the Heart, the Hmong Kitchen in America

Sami Scripter's groundbreaking book, Cooking from the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America, written with co-author Sheng Yang, has just been released in paperback. When it was published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2009, it was the first published collection of Hmong recipes since the Hmong people adopted a written language in the 1950s, and it represented a cultural milestone for the widely dispersed Southeast Asian community. I wrote a story about Scripter and Yang for the Oregonian's FoodDay, and I'm republishing it here.

The Hmong people had no written language until the 1950s, so it makes sense that it took until now for them to get their first cookbook.

But to tell the story of the book, we need to go back to 1980. That's when Sami Scripter, the coordinator of the talented and gifted program at Rigler Elementary School in Portland, met Sheng Yang, a young Hmong (pron. "mong") immigrant, in her English as a Second Language class. Scripter's desk was in one corner of the room, and she was taken with the inquisitive and self-possessed 11-year-old.

But to tell the story of the book, we need to go back to 1980. That's when Sami Scripter, the coordinator of the talented and gifted program at Rigler Elementary School in Portland, met Sheng Yang, a young Hmong (pron. "mong") immigrant, in her English as a Second Language class. Scripter's desk was in one corner of the room, and she was taken with the inquisitive and self-possessed 11-year-old.

"Sami was always very helpful," Yang says. "I'm a very nosy person. I'd go up to Sami and she would always answer my questions."

Portland had seen a large influx of Hmong from refugee camps in Thailand as part of a resettlement program in the late '70s. To welcome the newcomers to Rigler and expose the community to Hmong culture, Scripter organized a talent night that showcased Hmong songs, dance and food.

Yang was scheduled to perform in the show and, since they lived just two blocks apart, Scripter would often give her a ride home from practices. Yang's mother would invite Scripter to stay for dinner, and eventually the two families formed a strong friendship. Knowing how fond Scripter and her family were of Yang, her parents asked if it would be possible for her to come live with the Scripters.

"Among Hmong families, children will often go to live with an aunt and an uncle for a year," Scripter says. "It's considered a learning experience. So it wasn't out of character for their culture, and we could help Sheng with her English and her classes."

"When I moved in with Sami and her husband, Don, he actually built bunk beds for me and (Scripter's daughter) Emily," Yang says. "Ever since then, Sami and Don and their family have been a part of our family."

Fruit Cocktail

As with many cultural exchanges, it quickly became a two-way street. While Yang's English improved and she learned to appreciate tomatoes, she also began teaching Scripter and her new American family about Hmong cooking.

More than once this new road required some negotiating, as when Yang was making a variation of the traditional Hmong green papaya salad. Since green papayas were not readily available in stores at the time, Yang was making the salad with carrots.

"She needed a certain tool but didn't know the American word for it," Scripter said. "Of course, I didn't have it in my kitchen, so we ended up going back to her house. It turned out it was a mortar and pestle."

Portland's Hmong population is estimated to be around 4,000, relatively small compared with the larger communities found in Minneapolis and Sacramento.* Most came here as refugees after the Vietnam War, when they were targeted by the communist government in Laos for helping the U.S. during the war.

In the mountains of Laos, they'd believed in a form of animism and used shamans and herbal remedies. Wild ingredients such as lemon grass, bamboo and rattan shoots, and banana blossoms, as well as herbs and seasonings such as cilantro, green onion, galangal, ginger, hot chiles, fish sauce and black pepper were commonly used.

Most food was cooked over an open fire, sometimes heated in a pot of broth or wrapped in banana leaves and steamed. Compared with the fiery cuisines of many of its Southeast Asian neighbors, the cooking of Laotian Hmong was fairly mild and focused on subtler herbs and broths.

As in many traditional cultures, food often played a central role in most ceremonial gatherings, whether for the new year, weddings and funerals or for shamanistic healing rituals. To this day, many Hmong foods have some spiritual or cultural significance.

But because the Hmong had no written language, until very recently they were dependent on an oral tradition to pass on their cultural heritage, and many of the recipes for these significant cultural foods had not been recorded.

Which is where Scripter and Yang's unique relationship enters the story.

Having written down Yang's recipes over the years, Scripter and Yang, now an adult, began talking about creating a book that would not only introduce Hmong foods to Western audiences but would also be a written record of the traditions that were becoming increasingly diluted by the influence of American culture.

"We wanted it to be representative of Hmong people across the United States," says Scripter, "not just what came out of Sheng's kitchen." She started traveling to different Hmong communities around the country, asking who made the best traditional foods, such as larb or cracked crab.

"So I'd go over to her house and cook cracked crab," Scripter says. "Then I'd ask what else people like that she cooks, and one thing led to another."

One interview was particularly significant and underscored why Scripter felt it was so important to write the book, which she and Yang had decided to call "Cooking From the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America."

"I met a woman and she really wanted to tell me this story," Scripter said of her first meeting with Mai Xee (pron. "my see") Vang.

Vang's mother, Ka Kue, had immigrated without being able to read or write, so she began teaching her mother to read and write English. It soon became apparent that her mother preferred her own language, so Vang taught her mother to read and write in Hmong.

After Vang married and left home, her mother fell ill and eventually succumbed to kidney disease. "Unbeknownst to her children, when Ka Kue knew she was really ill she started writing a journal," Scripter says. "It's all about her life in Laos and is illustrated with her own drawings, with all the traditional farming and cooking implements.

"Because she knew she would die, she wanted her children to have her voice to tell them what to do to be a good Hmong man or woman," Scripter says.

After the funeral, Vang and her siblings found their mother's journal, wrapped tightly in a Hmong skirt and concealed in a basket under her bed. Under the little drawings in her journal, Kue had written, "Peb ua neej nyob yuav tsum muaj tej nuav mas txhaj paub ua peb lub neej nyob. Nuav yog qov ob huv peb lub neej." Roughly translated, her words mean, "In our lives, we must have these things in order to make a good life."

Recipes from the original article include Trout Xav Lav Ntxuag Fawm (Trout Salad with Vermicelli Noodles), Kua Quab Zib rau Ntses Trout Sav Lav (Sweet and Sour Fish Sauce for Trout Salad), Laj Nqaij Nyuj Xaj los yog Suam (Grilled Beef Larb), Kua Txob (Hot Chile Condiment), Qab Zib Khov Xyaw Kua Mav Phaub thiab Tiv Hmab Txiv Ntoo (Coconut Gelatin With Tropical Fruit Cocktail).

* Current estimates for the Hmong population in Oregon are just under 3,000.

Photo of chicken larb by Robin Lietz from Cooking By Heart.

"I'm immensely proud of the work the District has accomplished during my 10 years on the board," Guebert said, "From helping new farm businesses with our Headwaters Farm Incubator Program, funding land purchases to protect farmland, natural resource land, and parks throughout the district, and doing the hard work to recruit and retain a dedicated staff of employees."

"I'm immensely proud of the work the District has accomplished during my 10 years on the board," Guebert said, "From helping new farm businesses with our Headwaters Farm Incubator Program, funding land purchases to protect farmland, natural resource land, and parks throughout the district, and doing the hard work to recruit and retain a dedicated staff of employees."

As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting

As part of the campaign, OAT will also be hosting

There are many kinds of meals. There are those that simply feed you, those that feed your soul, and those that are so memorable that they rate right up there with the best experiences of your life. A meal at Joel Robuchon’s in Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel is such an experience. Robuchon was named “Chef of the Century” by the Gault Millau in 1989 and had 32 Michelin stars, the most of any chef, at his time of death from pancreatic cancer in 2018.

There are many kinds of meals. There are those that simply feed you, those that feed your soul, and those that are so memorable that they rate right up there with the best experiences of your life. A meal at Joel Robuchon’s in Las Vegas MGM Grand Hotel is such an experience. Robuchon was named “Chef of the Century” by the Gault Millau in 1989 and had 32 Michelin stars, the most of any chef, at his time of death from pancreatic cancer in 2018.  So it is with great enthusiasm that Ginger embraces the hot new trend shepherded to fame by TikTok creator Justine Doiron: The Butter Board. Most of you are familiar with charcuterie boards—tasty combinations of meats and cheeses, along with complementary accompaniments such as fruits and nuts that make for great snacking and conversation when served among friends and family. Well, a Butter Board is a similar concept, only the main attraction is the excellent quality butter that has been creatively enhanced and surrounded by pieces of bread and crackers.

So it is with great enthusiasm that Ginger embraces the hot new trend shepherded to fame by TikTok creator Justine Doiron: The Butter Board. Most of you are familiar with charcuterie boards—tasty combinations of meats and cheeses, along with complementary accompaniments such as fruits and nuts that make for great snacking and conversation when served among friends and family. Well, a Butter Board is a similar concept, only the main attraction is the excellent quality butter that has been creatively enhanced and surrounded by pieces of bread and crackers. The thing that is so wonderful about this idea is that it is relatively simple to prepare, and you can get as creative as you want with the combinations of ingredients. First, you start with fabulous butter. Do not skimp here! Here at the Beaverton Farmers Market, we are lucky to have the gorgeous butter made by our friends at

The thing that is so wonderful about this idea is that it is relatively simple to prepare, and you can get as creative as you want with the combinations of ingredients. First, you start with fabulous butter. Do not skimp here! Here at the Beaverton Farmers Market, we are lucky to have the gorgeous butter made by our friends at

Lately I've found some mighty meaty collars, almost like a fish steak with wings, at

Lately I've found some mighty meaty collars, almost like a fish steak with wings, at