Dungeness MIA This Holiday: Crabbers Getting Lowballed by Processors

With price negotiations stalled and the entire West Coast fleet

essentially tied up at the dock,

it looks like holiday crab feeds are going to have to wait.

Every New Year's Eve for the last several years we've gathered with friends for a crab feed. While our get-together wasn't going to be possible in this year of COVID, we wanted to keep the tradition going by having our own crab feed here at home, maybe even ZOOM-ing with our friends for at least a toast, if not the whole feast.

But in calling around, there was almost no whole, fresh crab to be found. Odd, since the season for the 2020 commercial Dungeness season opened on December 16.

Is this yet another reason to curse 2020?

In doing a little digging, it turns out that the curses would be more appropriately flung at the large fish processors that dictate the price they're willing to pay crabbers for this quintessentially ephemeral delicacy. The 800-pound gorilla among these processors is Pacific Seafood with 3,000 employees and $1 billion in annual revenue. Next largest is Bornstein Seafoods with 170 employees and $40 million in annual revenue, followed by Hallmark Fisheries and Da Yang Seafood.

According to Tim Novotny of the Oregon Dungeness Crab Commission—an industry-funded agency that's part of the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s (ODA) Commodity Commission Program—each of the state's six major ports has a team of negotiators that, together, meet and propose the price crabbers believe their catch is worth each season. In 2020, the price they went to the processors with started at $3.30 per pound for live crab.

Hallmark and Bornstein countered with a price of $2.20 per pound, then Pacific Seafood came in with a proposal of $2.50 per pound, all roundly dismissed by fishers as barely enough to cover their costs, not to mention not worth risking their lives for in winter's cold, rough seas. Crabbers then came back with a price of $3.20 per pound, which was rejected by processors.

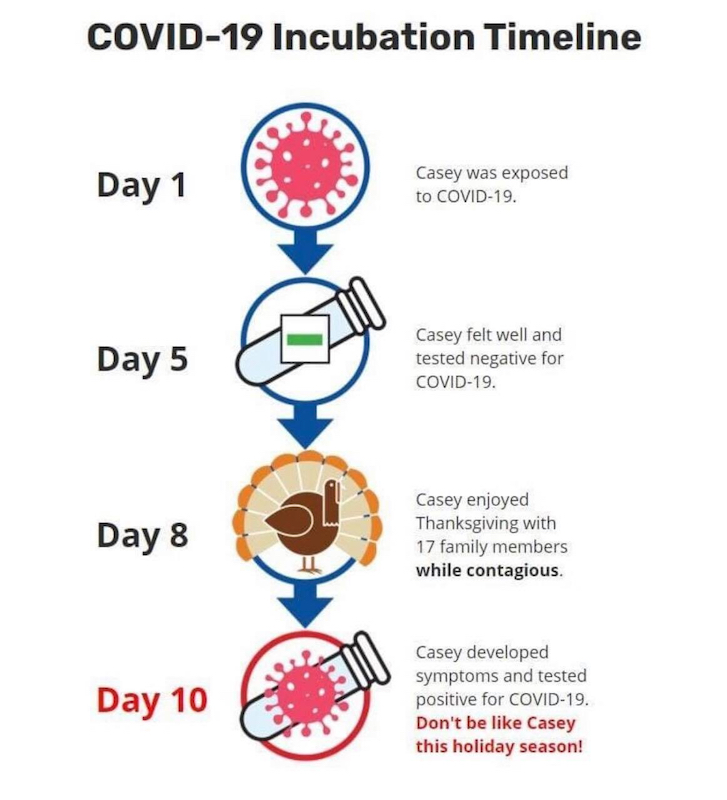

The pandemic is playing a part in negotiations as well, with crabbers saying if crews experience an outbreak it could shut down their season entirely. For their part, processors are nervous about the market for crab, with restaurants only open for takeout and not ordering in their usual volume, and with retail customers hesitant to venture out to stores to buy product.

Pacific Seafood—which Novotny described as "the straw that stirs the drink" because of its position as "the big dog" in the market—is irked that it's being blamed for ruining holiday celebrations. An article for KCBY in Coos Bay quotes Jon Steinman, vice president of processing at Pacific Seafood, as saying "the notion that Pacific Seafood is holding up the Dungeness season is absurd.

"'We are one of many other major buyers on the West Coast,' Steinman said in a statement. "We have to do the best we can for our customers, our fishermen, and our team members who are counting on us to run a good business and be here for this season and years to come.”

It is possible that the ODA could get involved in the negotiations if a request is made by both the crabbers and the processors.

"By law, Oregon allows [processors] and fisherman to convene supervised price negotiations with oversight from the ODA," said ODA's Andrea Cantu-Schomus in response to my e-mail. "A request for state-sponsored price negotiations was made to ODA, [but] ultimately there was not enough participation [from both sides] to hold negotiations."

The opaque nature of the negotiations is frustrating to Lyf Gildersleeve of Flying Fish, a sustainable seafood retailer in Portland, who would like to see a more transparent process rather than what he terms a "closed-door conversation" between the haggling parties. "Processors always lowball the price to make another fifty cents per pound," he said, noting that, for the most part, "people will pay whatever it takes" to have their holiday crab.

And as much as I'd like to make this about me, the delay in setting a price for this year's Dungeness catch isn't just inconveniencing my holiday plans, it's hurting the whole economy of the coast. From fishing families to retailers to the small coastal towns already hard-hit by the pandemic, it's compounding the devastation wrought by job losses and the lack of tourist dollars,.

So, with price negotiations stalled and the Oregon and California fleets* essentially tied up at the dock, it looks like our New Year's crab feed is just going to have to wait.

You can find tons of recipes in my Crustacean Celebration series.

* Washington's Dungeness season has been delayed until Jan. 1 due to elevated levels of domoic acid, a marine toxin.

UPDATE: After more than three weeks on strike, on Friday, January 8, commercial Dungeness crab fishermen accepted an offer of $2.75 per pound from Oregon processors, a significant reduction from the crabbers' previous proposal of $3.25 per pound.

Find tons of recipes in my Crustacean Celebration series.

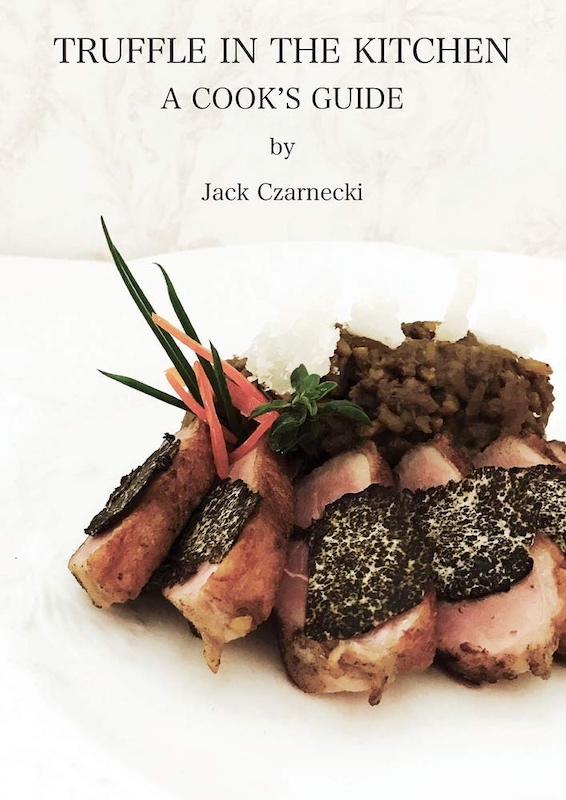

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed  His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle.

His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle. No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven

No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven  The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking.

The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking. I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his

I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his  Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original.

Styrian pumpkin seed oil, kürbiskernöl, is a Protected Geographic Indication (DOC, AOC equivalent) reserved for oil pressed from seeds grown in Styria. There are especially adapted machines for harvesting the fruits and extracting their seeds. For extraction of the oil, the washed and dried seeds are milled, turned into a paste with addition of water and salt, roasted and then pressed for their oil. As with other finely-crafted foods, other places have scrambled to find ways to cut corners and manufacture something cheaper, lacking the spirit of the original. Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits.

Those original purchased seeds were a messy lot as well, producing seeds with qualities that made them less than desirable for simply eating whole. More widget thinking. Most problematic were seeds that split or germinated in the fruit; some even had roots. These seeds contained the bitter compound cucurbitacin and spoiled one’s gustatory moment. These very bitter, toxic compounds are water-soluble, so they may not affect quality of the oil, but when chewing the seed their awfulness lingers. The seeds also varied in size and some retained a hard rim detracting from their pleasure for consumption as whole seeds. Undeterred, we decided to embark on improving the plant's genetics and our management of the fruits. Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait.

Fruits in the Cucumber family typically have three placentas forming six paired rows of seeds, easy to see in the lefthand fruit. (That fruit is not very interesting, aside from being a perfect fruit for setting aside as a seed source. For our purposes, an uninteresting pumpkin is the gold standard.) Each placental pair is usually pollinated by a cluster of pollen grains from a single plant. You see this by looking closely at the interesting fruit on the right. The seeds in the lower lefthand placental pair have not split, while the seeds of the other two pairs have opened up showing their white cotyledons. This shows that the splitting of the seeds in the fruit has a genetic component. The observation means we can reduce seed splitting by selecting against the trait. Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.

Alas, as those seeds dried they smelled exactly like vomit, an awful odor that lingered even when they were dry. We ended up giving nearly 150 pounds of dried pumpkin seeds to our friend’s pigs. A very expensive loss for us. Just the harvest, extraction, cleaning and drying of a pound of seeds required a half hour of labor. That did not include the growing of the plants, an additional expense. The last two years entailed taking baby steps to figure out where we went wrong.

And when you're in the middle of a pandemic and can't pop out to the store to pick up some ingredients on the fly to make a special dish, it's especially necessary to be creative with what you've got on hand. Which is where casseroles or stir-fries come in handy, since they cover all the food groups—starch, veg, protein—and are warm, belly-filling and can be zhooshed with spices, herbs and condiments to tickle any palate.

And when you're in the middle of a pandemic and can't pop out to the store to pick up some ingredients on the fly to make a special dish, it's especially necessary to be creative with what you've got on hand. Which is where casseroles or stir-fries come in handy, since they cover all the food groups—starch, veg, protein—and are warm, belly-filling and can be zhooshed with spices, herbs and condiments to tickle any palate.

Cornelius writes in

Cornelius writes in