Dorie Greenspan's Lemon Curd: Sunshine on a Cloudy Day

As I write this, I'm looking out my kitchen windows at snow-covered yards and roofs, listening to the crackle and crash of ice falling from our trees and the tapping sound of icicles dripping from our gutters. We've had one of our February dumps of snow followed by an ice storm that has left a quarter of the city without power, some of whom won't be reconnected for at least a week.

Fortunately, so far we have only experienced about an hour without power, though I've been forcing Dave to grind coffee in the electric grinder before we go to bed at night, just in case. Yesterday was Valentine's day, and Dave spent it smoking one of his signature briskets, as well as making a Japanese-style milk bread, which he's been obsessing over since reading about it on the King Arthur website.

Fortunately, so far we have only experienced about an hour without power, though I've been forcing Dave to grind coffee in the electric grinder before we go to bed at night, just in case. Yesterday was Valentine's day, and Dave spent it smoking one of his signature briskets, as well as making a Japanese-style milk bread, which he's been obsessing over since reading about it on the King Arthur website.

It's a sweetened, fluffy white bread that was perfect with the deep, moist, peppery smoked brisket and it soaked up the dark, salty juices like a champ. But you might well ask why I'm writing about brisket and milk bread in a post that's supposed to be about lemon curd. It's because for breakfast this morning we had thick slices of that slightly sweet, spongy bread toasted and spread with the Meyer lemon curd I've been making by the quart lately.

You know my "thing" about Meyer lemons, right? I've currently got two big Mason jars of preserved Meyer lemons curing in their salty brine in the fridge, and the puckery tang of my Meyer lemon tart reminded me I wanted to learn to make lemon curd. After all, the lemon filling is basically lemon curd, right?

I set about searching for an easy, simple recipe for curd and ran across one by Dorie Greenspan, who begins her biography with the words "I burned my parents’ kitchen down when I was 12 and didn’t cook again until I got married." Since then, luckily for us, she's written 13 cookbooks and is the "On Dessert" columnist for the venerable New York Times.

I set about searching for an easy, simple recipe for curd and ran across one by Dorie Greenspan, who begins her biography with the words "I burned my parents’ kitchen down when I was 12 and didn’t cook again until I got married." Since then, luckily for us, she's written 13 cookbooks and is the "On Dessert" columnist for the venerable New York Times.

Funny and smart, her writing is always delightful and, at the same time, down to earth, and her recipes—certainly the ones I've tried—are bullet-proof. The same proved true when I made her lemon curd, which she describes as having a "texture [that] is smooth and comforting and its flavor is zesty, a delicious contradiction."

It takes less than half an hour to make, assuming you've got lemons on hand—either regular or Meyer lemons will work—and the result, while fabulous on scones, biscuits or that toasted milk bread, is something you'll be tempted to sneak spoonfuls of when no one's looking.

And yes, I actually have her personal blessing to share it with you. Thanks, Dorie!

Dorie Greenspan's Lemon Curd

1 1/4 c. (250 grams) sugar

4 large eggs

1 Tbsp. light corn syrup (I made up a substitute using 1/2 c. sugar dissolved in 2 Tbsp. hot water)

3/4 cup (180 milliliters) freshly squeezed lemon juice (4 to 6 lemons)

1 stick (8 tablespoons; 4 ounces; 113 grams) unsalted butter, cut into chunks

Whisk the sugar, eggs, corn syrup and lemon juice together in a medium heavy-bottomed saucepan. Drop in the pieces of butter.

Put the saucepan over medium heat and start whisking. You want to get into the corners of the pan, so if your whisk is too big for the job, switch to a wooden or silicone spatula. Cook, continuing to whisk—don’t stop—for 6 to 8 minutes, until the curd starts to thicken. When it is noticeably thickened and, most important, you see a bubble or two come to the surface, stop; the curd is ready.

Immediately scrape the curd into a heatproof bowl or canning jar or two. Press a piece of plastic wrap against the surface to create an airtight seal and let the curd cool to room temperature, then refrigerate.

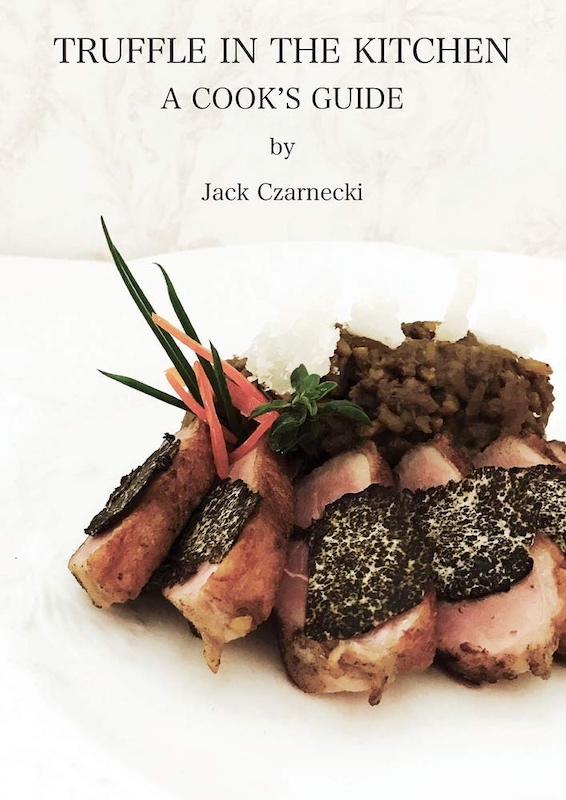

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed

If you want to know about the fungus among us, there is no better guide than mushroom guru Jack Czarnecki, founder with his wife Heidi of the famed  His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle.

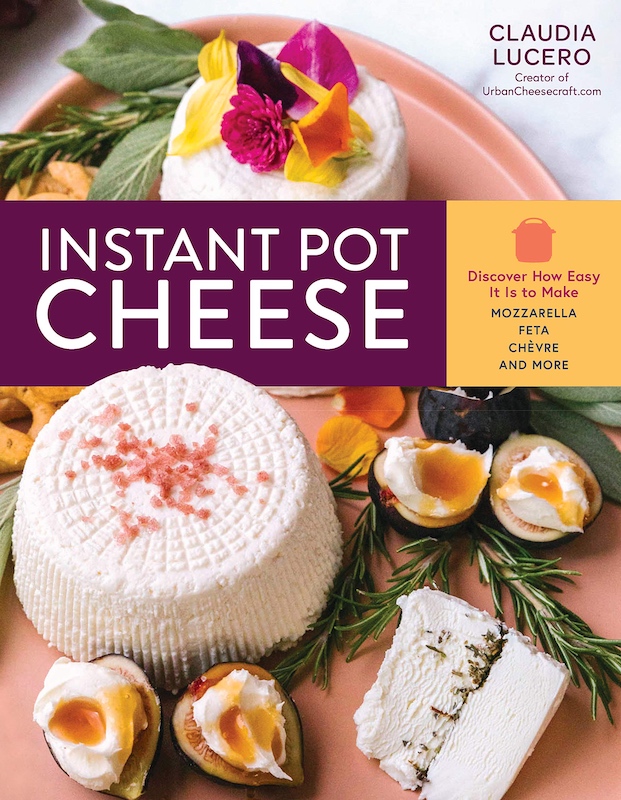

His latest effort is a cookbook, for sure, full of simple-to-prepare basics like truffle butter and oil, as well as what he terms "atmospheric infusions," along with recipes for main dishes and even desserts. But it also delves deeply into Czarnecki's background as a bacteriologist, discussing his theories on the complex relationship between our physiology and how it interacts with that of the truffle. No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven

No one I know has worked harder to spread the gospel of cheese and how easy it is to make at home than local cheese maven  The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking.

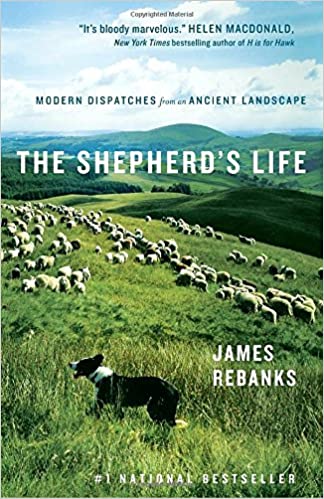

The viral success of the Instant Pot cooker got Lucero to thinking about how this appliance might be used to make cheese. After all, it can be used to do just about anything: caramelize onions, boil eggs, steam rice, so it seemed sensible to her that the cooker's accurate and consistent temperatures should make it an ideal tool for cheesemaking. I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his

I first became acquainted with James Rebanks through, believe it or not, his  Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,

Deeply rooted in the land Rebanks' family has farmed for generations,