Boardman Residents Sue Polluters Over Contaminated Drinking Water

A review of 30 recent studies lists the most prevalent risks associated with

ingesting nitrates as blue baby syndrome (methemoglobinemia), colorectal cancer,

thyroid disease, and neural tube defects, even at levels below regulatory limits.

The State of Oregon and federal agencies have known for more than 30 years that there was a serious problem with industrial and agricultural pollution of the water in Morrow and Umatilla Counties, yet residents of those counties are saying that next to nothing has been done about it.

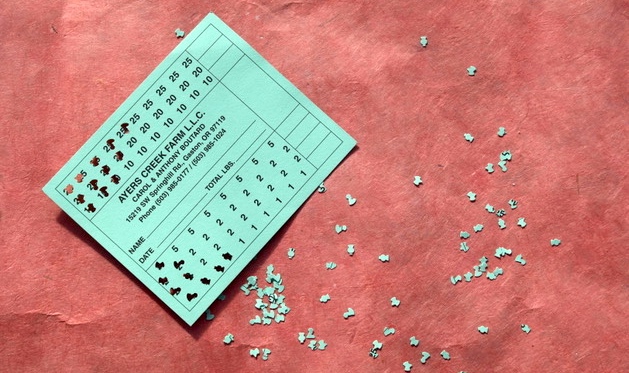

On February 28th of this year, five Boardman residents filed a class action lawsuit in federal district court in Pendleton accusing the Port of Morrow, Lamb Weston, Madison Ranches, Threemile Canyon Farms—a 70,000-cow megadairy that supplies most of the milk for Tillamook's products—and Beef Northwest Feeders of contaminating groundwater in Oregon’s Lower Umatilla Basin by dumping nitrogen throughout Morrow and Umatilla Counties. Attorneys estimate the issue affects upwards of 46,000 residents, many of whom are children.

Senator Jeff Merkley (back row, center) to discuss contaminated water in January of 2023.

Since 2017, I've written on Good Stuff NW about the damage caused by industrial agriculture starting with a post titled "Why I'm Quitting Tillamook Cheese." That post became the basis of an article for the news website Civil Eats, "'Big Milk' Brings Big Issues for Local Communities" which connected the dots between industrial agriculture and the health of the communities—along with the air and water—around these facilities, especially when, as in Oregon, they are regulated as "farms" and not the industrial facilities they actually are. Even back in 2017, the Oregon Department of Agriculture admitted that some wells used for drinking water contained nitrate levels over the federal maximum allowed.

A review of research published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in 2018 analyzed more than 30 recent studies on the effects of nitrates in drinking water, listing the most prevalent risks as blue baby syndrome (methemoglobinemia), colorectal cancer, thyroid disease, and neural tube defects, adding that "many studies observed increased risk with ingestion of water nitrate levels that were below regulatory limits." [Emphasis mine.]

“Defendants have dumped, and continue to dump, millions of pounds of nitrogen onto land in Morrow and Umatilla counties,” the lawsuit said. “Nitrogen in the ground converts into nitrates, which then percolate down to the water table in the Lower Umatilla Basin, polluting the subterranean aquifer on which plaintiffs and class members rely for their water.”

In an article in the Capital Press, Boardman resident Michael Pearson, one of the plaintiffs in the suit, said that his family relies on a private well. When he had his water tested in 2022, he was shocked to discover it contained many times over the nitrate level considered safe by federal authorities. When he had a filtration system installed to treat the water, it still remained well over the federal maximum.

Two other plaintiffs, Michael and Virginia Brandt, discovered their water was contaminated when they had it tested, but they couldn’t afford a filtration system. James and Silvia Suter said that nitrate levels in the water coming out of their taps is four times the federal maximum, but when they looked into drilling a well deeply enough to get to uncontaminated water, the cost was quoted at $24,000.

have tested several times over the federal maximum.

Oregon Public Broadcasting interviewed Steve Berman, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, where Berman compared the nitrate pollution in the Lower Umatilla Basin to the drinking water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where thousands of people were exposed to lead and other contaminants through the municipal water system.

"There's some very powerful agri-businesses and the port, they make a ton of money off dumping this polluted water, and they have a lot of clout. So no, I wasn't surprised," Berman said in an interview with KGW-TV for their "Tainted Waters" series. "I think it's gone on so long because a lot of the victims are low-income minorities who can't afford to hire lawyers, don't have a voice in politics. As I said earlier [in the interview] if this was happening to a wealthy suburb of Portland, it would have been stopped years ago.”

The plaintiffs are hoping not only to gain compensation from the defendants, but also to require them to clean up the basin's soil and groundwater, to get residents connected to a clean source of water, and begin medical testing of residents for health issues related to nitrate contamination.

Top photo: Sprinklers spraying wastewater at Threemile Canyon Farms (from its Facebook page). Photo of Sen. Jeff Merkley meeting with residents who are experiencing contaminated water. Photo of manure lagoon at Threemile Canyon Farms from Friends of Family Farmers.

Disclaimer: One of the defendants in the lawsuit, Beef Northwest, is the current incarnation of the Wilson ranch, founded by my great-grandfather in North Powder, Oregon, in 1889.

"We’re happy to announce that after many months, the debut of their full-service meat and seafood counter at Providore is here," said Kaie Wellman, co-owner of Providore along with her husband, Kevin de Garmo and their business partner, Bruce Silverman. "The 'protein' corner of the store has been transformed into a mecca for those who want to work closely with their local butcher and fishmonger to source top-quality, small-farmed meat and sustainably caught seafood."

"We’re happy to announce that after many months, the debut of their full-service meat and seafood counter at Providore is here," said Kaie Wellman, co-owner of Providore along with her husband, Kevin de Garmo and their business partner, Bruce Silverman. "The 'protein' corner of the store has been transformed into a mecca for those who want to work closely with their local butcher and fishmonger to source top-quality, small-farmed meat and sustainably caught seafood." A huge problem with our food system is that shoppers are often misled about what they're buying. Tilapia, a common farmed fish, is mislabeled as more expensive snapper—

A huge problem with our food system is that shoppers are often misled about what they're buying. Tilapia, a common farmed fish, is mislabeled as more expensive snapper—

Calling Providore's partnership with these two purveyors a "perfect marriage," Wellman added that "their sustainability standards are unmatched anywhere. These guys walk their talk."

Calling Providore's partnership with these two purveyors a "perfect marriage," Wellman added that "their sustainability standards are unmatched anywhere. These guys walk their talk."