Once Renowned Oregon Dairies Decimated by Factory Farms

How much is that grilled cheese sandwich worth to you?

It may seem like an odd question until you consider that the decline in American dairy farms has been catastrophic (see animation below). According to FarmAid, in 1934 some 5.2 million dairy farms dotted America’s countryside, but between 1997 and 2017, the U.S. lost half of its 72,000 remaining dairies and today fewer than 28,000 licensed dairy herds remain.

In Oregon, once renowned for the quality of its dairy products, one historian said that in 1914 there were 1,004 licensed dairies in Portland alone. A recent article in Portland Monthly states that the number of licensed dairies in Oregon dropped from around 500 in 1990 to 192 in 2020 and that, on average, Oregon is losing about six dairy farms a year.

Interestingly, while the number of individual dairy farms in Oregon has been dropping like a rock, the number of dairy cows has remained fairly steady. That's because of the influx of industrial factory farm dairies—aka "mega-dairies"—that have flooded into Oregon due to our lax environmental regulations that classify these industrial facilities as "farms" instead of the factories that they really are.

The largest is North Dakota-owned Threemile Canyon Farms, a 70,000-cow industrial facility that supplies the vast majority of the milk used to make Tillamook cheese and its ice cream, yogurt and other products. It's also one of the two largest in the United States, according to an article in Columbia Insight on mega-dairies' use (and abuse) of our water resources. Ironically it has called itself a "family farm" in public hearings in Salem.

As my friend, organic dairy farmer Jon Bansen noted on his tour of Threemile Canyon, "The scale is impressive, but the biology is horrifying."

Of the wells tested so far, around a quarter have contained high levels of the dangerous nitrates that have plagued the Lower Umatilla Basin since at least 1990.

Friends of Family Farmers (FoFF), an organization that advocates for Oregon's small family farmers, posted recently that mega-dairies have played a major role in driving dairy farmers off the land, stating that they over-produce and flood the market with cheap milk, making it impossible for small dairy farmers to compete, while externalizing their environmental and social costs on the state's taxpayers.

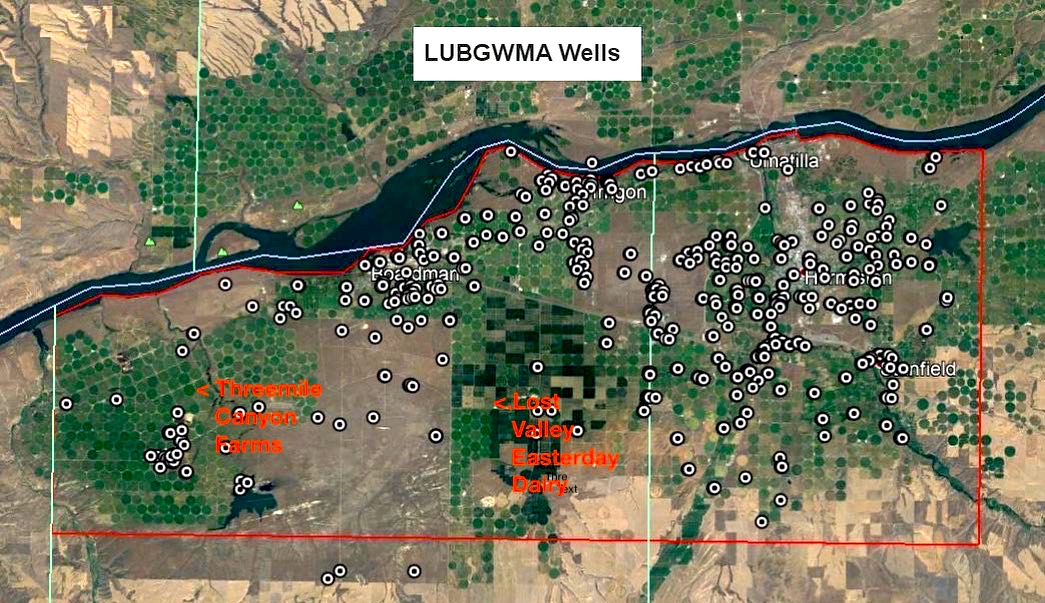

As an example, FoFF's post states that last May Governor Tina Kotek met with community members in Boardman—where several industrial agricultural facilities, including feedlots and mega-dairies, are located—where she set a deadline to test for nitrate contamination from agriculture from all 3,300 wells used by households (see map, above). Testing on that scale is a huge expense that will be borne by taxpayers rather than the polluters, but as of the deadline at the end of September state agencies had only managed to test 1,001 of the domestic wells in the Lower Umatilla Basin. Of the wells tested so far, around a quarter have contained high levels of the dangerous nitrates that have plagued the Lower Umatilla Basin since at least 1990.

It’s shameful taxpayers are left with the bill instead of agribusiness and industry

which have profited while contaminating the state's groundwater.

The federal government is stepping in to help with some of the cost to address the water crisis in the two counties affected, announcing $1.7 million dollars in federal aid to help deal with nitrate contamination in private wells. But according to Kristin Anderson Ostrom, Oregon Rural Action executive director quoted in the Hermiston (OR) Herald, "Folks can’t live out of 5-gallon bottles forever, and they shouldn’t have to. This is really just a long-awaited first step and there’s a lot of work to do to build on the testing we’ve already done.”

Ostrom added that it’s shameful taxpayers are left with the bill instead of agribusiness and industry, which have profited while contaminating the state's groundwater.

So what is having that grilled cheese sandwich worth to you considering the costs outlined above?

As I said in a recent post on social media, the fact that these industrial facilities were—and still are—allowed to operate on a federally designated, at-risk aquifer is outrageous. Oregon's taxpayers are and will be on the hook for the clean-up for decades while these extractive industries will be given a slap on the wrist (if anything) while continuing to operate.

Read my coverage of mega-dairies in Oregon, and why it's critical that we try to buy local when possible. Top photo of Mayflower Dairy delivery wagon from the fascinating website PDX History.

While the article primarily addresses how this lack of transparency affects institutional food procurement, the same problem exists in our supermarket aisles and on restaurant menus. Aside from the slippery definitions of words like "natural," "humanely raised" and "cage-free," the word "local" has achieved currency as a desirable label on food products.

While the article primarily addresses how this lack of transparency affects institutional food procurement, the same problem exists in our supermarket aisles and on restaurant menus. Aside from the slippery definitions of words like "natural," "humanely raised" and "cage-free," the word "local" has achieved currency as a desirable label on food products. Want to add more local spirits to your home bar by buying from a local distiller? Check first that those products aren't made from bulk spirits imported from a factory far from Oregon. Many local distillers advertise their products as "locally produced" when they're actually importing bulk spirits that they only have to pump into barrels and blend or age here—it's worth asking if the producers truly distill their own alcohol.

Want to add more local spirits to your home bar by buying from a local distiller? Check first that those products aren't made from bulk spirits imported from a factory far from Oregon. Many local distillers advertise their products as "locally produced" when they're actually importing bulk spirits that they only have to pump into barrels and blend or age here—it's worth asking if the producers truly distill their own alcohol. Rapport adds that while sourcing locally is encouraged, requiring vendors to buy from local sources can be problematic. "What if that farm runs out of what you need? What if the same item from two different farms, cabbage for sauerkraut for example, doesn’t taste the same and alters the final product you are making?" Plus, she notes, local products are likely more expensive than wholesale ingredients from a larger supplier.

Rapport adds that while sourcing locally is encouraged, requiring vendors to buy from local sources can be problematic. "What if that farm runs out of what you need? What if the same item from two different farms, cabbage for sauerkraut for example, doesn’t taste the same and alters the final product you are making?" Plus, she notes, local products are likely more expensive than wholesale ingredients from a larger supplier.