Flour Market Opens on Killingsworth with Classic Breads, Pastries and More

Lisa Belt loves people, but she loves baked goods even more.

"I love everything in this store," she said, sweeping her arm above the counter packed with baskets of freshly baked loaves of sourdough, baguettes, challah and caraway rye at her newly opened Flour Market on Northeast 30th and Killingsworth. Those golden loaves are in addition to the croissants, cookies, crackers, granola, biscotti, blondies and…well…you get the picture.

I myself am particularly fond of the pastelitos, squared layers of shatteringly crisp, flaked croissant dough that Matt, the croissant savant at the market's production bakery, whose family has roots in Puerto Rico, made and filled with cream cheese and a guava paste that an aunt sent in a care package. Belt describes the market's signature panforte as a "grown-up treat that goes perfectly with tea, coffee, wine, or eggnog and whiskey. (Ask me how I know.)" I'm thinking it would be the perfect dessert at the end of an evening with a dram of my homemade nocino—I'll keep you posted on that one.

The Flour Market retail store was born, oddly enough, out of the shutdown from the COVID pandemic. A few months before, Belt had been talking about buying the production bakery from the owners of Lovejoy Bakers, Marc and Tracy Frankel, which they'd created to supply breads for paninis for their Pizzicato Pizza locations. Lisa had been managing the bakery and Lovejoy cafés for nearly 10 years, and when the Frankels decided to retire and sell the business, she figured buying it was better than being out of a job herself, not to mention all the bakers and production staff who would be out on the street.

By the time COVID hit Belt had acquired several wholesale accounts and was able to keep most of the staff on at the production facility filling orders, and there was enough street traffic at its location near OMSI and the Eastbank Esplanade to do a brisk takeout business in pastries on Saturdays. Customers started asking if she could also sell them flour, yeast and sourdough starter for bread, ingredients that were in short supply due to the baking frenzy generated by the pandemic lockdown. The successful no-contact takeout business made Belt start thinking a retail location might be a good idea.

So with COVID restrictions easing and people being more comfortable meeting with friends indoors, the idea of opening a retail location made even more sense. It so happened that Biga, another project of the Frankel's, closed down its location on Killingsworth, right around the corner from Extracto Coffee, providing the perfect opportunity for Belt to act on her idea.

Plans for the future include a menu of items Belt refers to as "bread adjacent" like toasts with simple, seasonal toppings and a granola, yogurt and fresh fruit bowl, plus a menu of sandwiches geared to the market's plethora of savory loaves. She's also got ideas for a specialty "bread of the month," perhaps a honey whole wheat that's currently in development with her team at the bakery or, in a nod to her Northern European ancestry, a traditional Danish rye bread called rugbrød or Swedish limpa, a lighter rye with a hint of orange that her mother used to make for the family when Belt was a child.

With a long history in managing restaurants and food establishments in Portland—overseeing the reboot of Genoa and its sister bistro, Accanto, running World Cup Coffee's stores, and her work at Lovejoy—she knows how critical it is to have a business that not only works for her but also for the employees. So if you ask, as one customer did recently, if Belt had made the mountains of baked goods herself, she'd respond by laughing and shaking her head, then proceed to point at each item on the counter and name the person who'd made it.

Oh, and did I mention that it's a little over a half hour's walk from my front door? Talk about an opportunity!

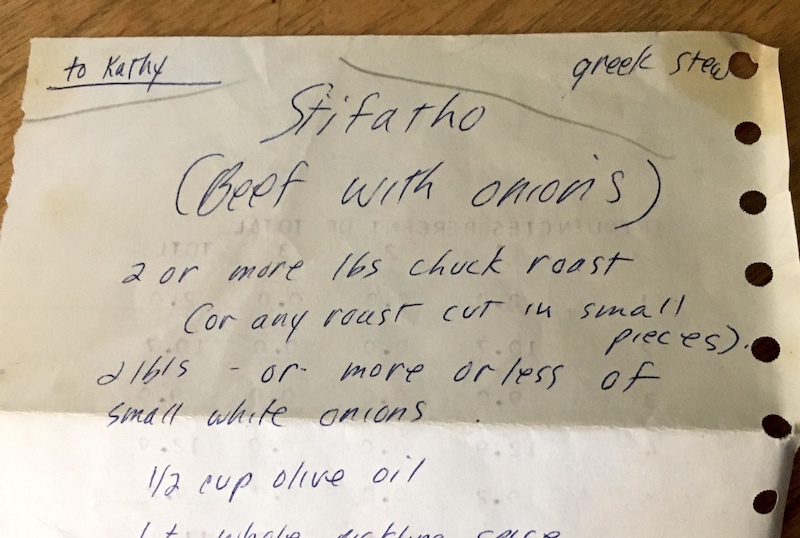

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

My first introduction to this particular stew was waaaaaaay back in high school when I became friends with a young woman who lived in our suburban neighborhood with its cookie-cutter ranch houses and striving white-collar families. Exotic in my stolidly middle-class experience, their house was littered with Balinese art and South Asian throws. Shelves of books rather than American colonial furniture were the focus of their decor, and when I was lucky enough to be invited for dinner they made curries and ethnic stews rather than noodle casseroles.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering.

He was raised in a Quaker family in the Midwest where his father worked on Peace Education with the American Friends Service Committee. He attended a Quaker high school, earning spending money as a bike mechanic, which continued into college where he majored in mechanical engineering. Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.

Volk transferred the skills he was developing in his volunteer work with rural farmers, applying their techniques to smaller-scale urban projects. From Palo Alto, Volk moved back east to work on projects in Washington, DC, eventually working his way back to Sauvie Island Organics here in Oregon, helping to start Skyline Farm, a five-acre project to supply the produce for Meriwether's Restaurant in Northwest Portland.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

My mother was much more comfortable cooking red meat, what with her upbringing in an Eastern Oregon cattle ranching family. When we did have fish, it was most often from a can—tuna or the dreaded canned salmon, which was unceremoniously dumped in a dish, the indentations of the rings from the can still visible on its surface. Any whole fish tended to be less than absolutely fresh, requiring lots of what was called "doctoring" to cut the fishiness.

When I wrote recently about

When I wrote recently about  With thicker-skinned citrus like oranges and lemons it'd be best to just use the outer peels, since their pith can be bitter, though with thinner-skinned fruit like Meyer lemons and tangerines (and their small round cousins) you can use the whole peels. And of course I'd recommend only using organically grown citrus, since a wide variety of toxic chemicals and sprays are used on conventionally grown citrus trees and fruit.

With thicker-skinned citrus like oranges and lemons it'd be best to just use the outer peels, since their pith can be bitter, though with thinner-skinned fruit like Meyer lemons and tangerines (and their small round cousins) you can use the whole peels. And of course I'd recommend only using organically grown citrus, since a wide variety of toxic chemicals and sprays are used on conventionally grown citrus trees and fruit.

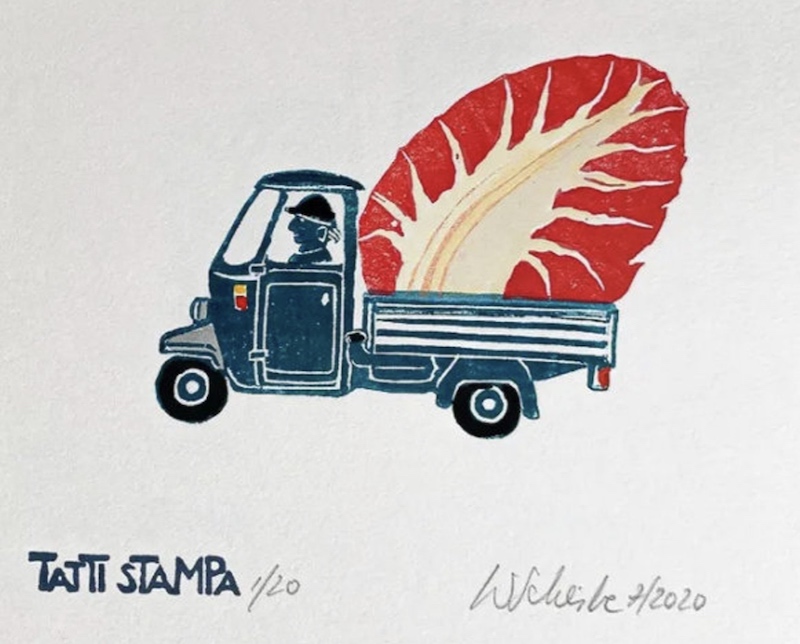

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family.

Radicchio season has been glorious this year, as evidenced by the gorgeous abundance of varieties at farm stands, farmers' markets and greengrocers. Not only has the weather been spectacular for this late fall crop, but more local farmers than ever are growing these slightly bitter members of the brassica family. So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.

So in late fall, my heart leaps when I see the first heads of Treviso and Castelfranco at the markets, and I can't seem to get enough of them in salads, chopped in wide ribbons and tossed with other greens and fall vegetables like black radish and fennel. I've also discovered an affinity between radicchio and our own hazelnuts—I've been crushing roasted hazelnuts and scattering them with abandon, where they bring a sweet counterpoint to the bitter notes of the chicory.

One day it struck me that I was wasting a heck of a lot of perfectly fine fruit juice, not to mention zest, that could be used in cocktails, desserts, salad dressings and any number of other recipes. You know the ones, where they call for a teaspoon of juice or a pinch of zest or a wedge for garnish, only requiring a portion of the whole.

One day it struck me that I was wasting a heck of a lot of perfectly fine fruit juice, not to mention zest, that could be used in cocktails, desserts, salad dressings and any number of other recipes. You know the ones, where they call for a teaspoon of juice or a pinch of zest or a wedge for garnish, only requiring a portion of the whole.